Format

Deal Profiles

City

Philadelphia

State/Province

PA

Country

USA

Metro Area

Philadelphia

Project Type

Multifamily Rental

Location Type

Other Central City

Land Uses

Fitness Center

Multifamily Rental Housing

Retail

Keywords

Adaptive use

Crowdfunding

Deal profiles

Dealprofiles

Historic preservation

Historic tax credits

Loft apartments

Neighborhood retail center

Site Size

0.55

acres

acres

hectares

Date Started

2013

Date Opened

2016

AF Bornot Dye Works is a loft apartment and retail project that involved the adaptive use and restoration of three timber and concrete factory buildings north of Center City Philadelphia. The three four-story buildings include 17 rental residences on the upper levels and 13,210 square feet of retail space across two lower levels. The developer, MMPartners, built upon 15 years of experience renovating and building scores of residential and retail properties in the nearby Brewerytown neighborhood. The $10.7 million development was funded with a conventional loan, federal and state historic tax credits, a city incentive loan, partner equity, and a $375,000 mezzanine loan from an online crowdfunding platform.

The Site and Neighborhood

The site comprises three low-rise loft buildings at Fairmount Avenue and 17th Street, less than a mile north of Philadelphia’s City Hall. Fairmount is at the north edge of Spring Garden, an area of large Victorian rowhouses bordered by a former industrial corridor along Broad Street.

In 2013, the city of Philadelphia suggested that MMPartners bid on the then-vacant Bornot buildings when the Spring Garden Community Development Corporation offered them for sale in 2013. The CDC, which had built new rowhouses throughout the small neighborhood a mile north of Center City, had purchased and mothballed the vacant industrial buildings years earlier.

The Initial Idea

In 2012, the CDC drew up plans to renovate the buildings with 13,210 square feet of neighborhood service retail, plus spacious loft apartments and off-street parking. “When we were brought in,” says Waxman, “we put a big value on the retail. Every other developer thought the retail was the albatross for the project, but we felt that this retail had a lot of value, and we were able to pay more. We knew we could land quality retail.”

That confidence in retail leasing stems from MMPartners’ experience in the nearby north Philadelphia neighborhood of Brewerytown. In 2001, Waxman says it was “where a 24-year-old could buy an entire block of shells” without a significant capital outlay. Rehabilitating eight abandoned rowhouses along its main street into 16 apartments and two storefronts launched a virtuous cycle as new amenities built upon existing projects. Waxman points out that “retail drives residential [demand] in the city,” and creating a neighborhood where residents “can walk to everything [they] need—or at least what [they] can’t order online—on a daily basis” has tremendous appeal.

The Idea Evolves

MMPartners’ track record was critical when the general contractor left the job several months into construction—setting the project schedule back by almost a year. William Bostic, president of Axis Construction, recalls spending nearly a month “analyzing what they had done and what needed to be done, figuring out anomalies in the contract,” redoing and reapproving drawings, sorting out unpaid invoices, and ultimately agreeing on a new price.

“Another bank might have called default right there,” says lending officer David Segal, but “the sponsor said what the problem is and how they’re going to fix it and get the work done. They accomplished that, and got the bank comfortable in a timely fashion. We are their partners in the project—so if it’s a problem for them, it’s a problem for us, too.”

Financial Overview

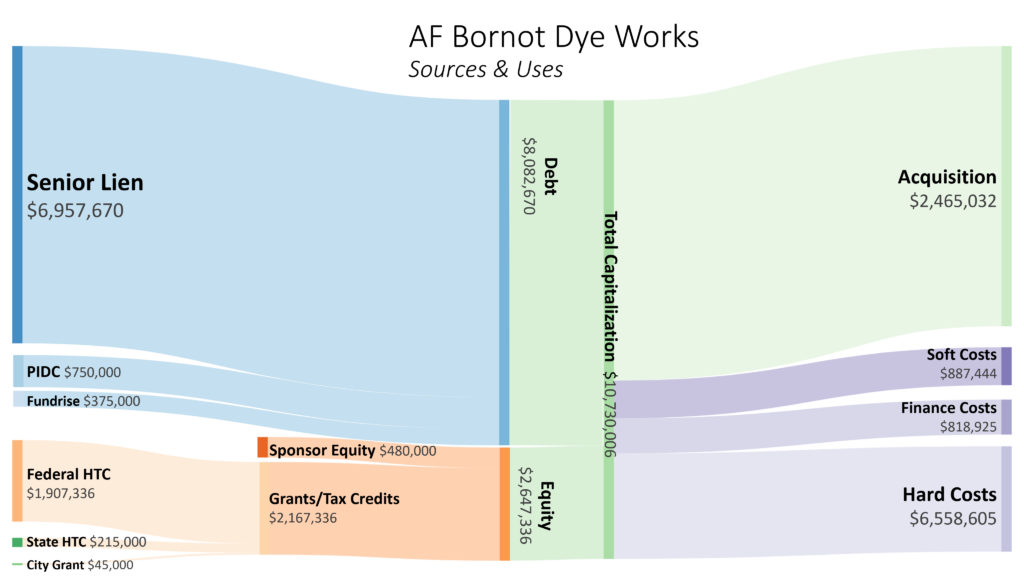

Waxman is particularly proud that a $10.5 million investment was leveraged with sponsor equity of less than 5 percent of the project budget. A construction loan covered 65 percent of the project budget, two junior liens accounted for about 11 percent, and syndicated federal and state tax credits, plus a city façade grant, paid for 20 percent.

Although bringing together this capital was a tremendous learning experience, Waxman notes that “if we did this project today, we would have done this much more traditionally.” Lenders have become savvier about urban residential and about historic tax credits in particular. Some lenders now do “one-stop” lending for historic projects, pairing a senior construction loan with a junior bridge loan that is repaid from the pending credits.

Historic Tax Credits

Over $2 million in equity funding resulted from historic preservation tax credits available to the project. Because it involves substantial rehabilitation of income property located within a National Register–listed historic district, the development qualifies for a federal income tax credit equal to 20 percent of the cost of construction. PNC Bank syndicated the federal tax credit, resulting in net proceeds of $1.9 million.

In addition, Pennsylvania is one of 33 states that offer state income tax credits for historic preservation. Unlike the unlimited federal program, this relatively new program was funded at just $3 million for a state with countless old buildings. Nonetheless, MMPartners beat the odds and was one of 15 recipients of Pennsylvania’s state historic tax credits in 2015, winning a lottery for a $250,000 allocation that net the project $215,000 in equity.

Junior Lien

The Philadelphia Industrial Development Corporation (PIDC) was happy to lend for the project’s substantial retail component. MMPartners’ previous work developing office and retail properties, in particular the renovation of a mill in the Manayunk neighborhood, into offices and several restaurant fit-outs, had introduced them to PIDC’s incentive financing for job-creating developments like retail, office, and industrial buildings.

PIDC’s capital project loans provide up to $750,000 in junior-lien debt, with a minimum of one new job created for every $35,000 lent. The loan terms are attractive, with an interest rate of half of prime rate (2.75 percent, in this instance) and a loan term of up to 15 years. Because much of PIDC’s loan funds come from government sources like the Small Business Administration, its upfront documentation requirements can be daunting. “Once you’ve gone through their process once,” though, “it becomes very easy,” says Waxman.

Senior Lien: Locating the Lender

Most of the $10.7 million project budget for AF Bornot Dye Works was funded with a conventional $7 million construction loan from Susquehanna Bank, a regional bank that has since been acquired. The construction lender was located through a broker, although Waxman notes that “Philadelphia is a big city, but it’s a small place,” where most deals happen through a handful of regional banks that are active in development lending.

Segal, senior vice president at TriState Capital Bank, was MMPartners’ loan officer at Susquehanna at the time. He says that he “had known about [MMPartners] for years” through that broker, but “had turned down two or three of their [Brewerytown] deals in the past”; the projected rents did not have concrete comparables and therefore did not match the bank’s risk appetite. Segal says that in retrospect, “his model’s been proven. I was wrong, and he was right, but I’m a bank—not an investor… and I just wasn’t willing to risk my employer’s money.” Waxman says that smaller banks stepped in for those projects.

Segal’s curiosity was piqued, though: “In my business, you have to keep in touch with people who will be performers later.” When the Bornot deal came around, then, the name was familiar. In this case, “we were pretty flexible and upfront with the things we were going to care about, which matched well with the things they were going to care about.”

Waxman says that, once stabilized, the project was refinanced with a nonrecourse permanent loan from a large national bank.

Senior Lien: Underwriting

Segal knew that Spring Garden “was a proven apartment market, where we had some comparables. But in terms of commercial… Fairmount has not been known as a retail hotbed.” Waxman notes that they required that 50 percent of the retail be preleased, and that the corner space went to a local bank. “In the midst of this deal, [that bank] was bought out” by a larger bank, adds Segal, “and in terms of credit [risk], the deal got better automatically.” The hurdle was easily achieved in the end: over 90 percent of the retail leased by the time the loan closed, a feat that Waxman attributes to closely working with the CDC and local broker MSC Retail.

Doubts about commercial leasing were also why Segal says that “the subordinate debt [from PIDC] was so important… It spread some of the risk.” PIDC and other public loans were key exceptions to what Segal says was a general policy of avoiding subordinate liens.

The complexity of what Segal calls “all these different sources that add up to a very interesting capital stack” did not faze Segal, who says that “we were comfortable with equity from a bunch of different places.” He continues, “Banks don’t view interesting as bad necessarily, but it’s up to the sponsor to explain and present it as such… to show that all the other funds coming in are real cash into the project.”

Yet not every bank will take the time to listen to such a presentation, he says: “If they have an off-the-shelf product description, that’s not the right lender. You need somebody to design a loan for something like this.”

Mezzanine Loan

MMPartners also used crowdfunding to finance the project. Fundrise, an online crowdfunding platform, made a three-year, $375,000 unsecured mezzanine loan to AF Bornot Dye Works, with 8 percent paid quarterly and 10 percent accrued until maturity. Fees paid included a 2 percent origination fee and a $5,000 due diligence fee.

Waxman “read about [Fundrise] before they launched” and reached out to get set up on the platform. He wanted to “put up a deal that we knew we could get done,” as a way to build goodwill and a track record with the platform’s investors. That first project was already under construction, with all funding already secured, but allowed MMPartners to cash out some of its equity before permanent financing.

Ben Miller, cofounder of Fundrise, calls MMPartners “the quintessential Fundrise developer. Our sweet spot has been in the space too big for people, too small for large funds.” This often means that projects with budgets between $5 million and $50 million and particularly projects that involve complicated urban infill sites. Typically, Fundrise buys out about half the sponsor equity as an unsecured preferred-equity or mezzanine-debt position, which can bring a project’s loan-to-cost ratio up to 85 to 90 percent. Preferred equity caps offer “a better risk-adjusted return,” says Miller, with limited upside potential and downside risk. Miller notes that this funding “looks like equity to the [construction lender], but it’s senior to the developer.”

Waxman notes that marketing deals via the platform has helped him “meet some investors who have been great to work with,” especially as his firm’s larger deals are attracting interest from private-equity firms.

Lessons Learned

Local engagement. Local stakeholder engagement was not limited just to the approvals phase for AF Bornot Dye Works. Rather, neighbors defined the project’s parameters from the very beginning. Neighbors’ enthusiastic support helped with retail leasing, given that the CDC has already identified a ready market for retailers it specified, such as the gym and yoga studio that filled second-floor space.

Adjacencies. Developing residential in urban neighborhoods can be tremendously rewarding—but neighborhoods revolve around retail, which needs careful cultivation. The synergies between urban residential and retail markets usually occur at the neighborhood scale, which is difficult (but not impossible) for a single small developer to influence. In-building retail can build value even for small-scale residential projects, but requires a broader customer base.

Creative finance. Emerging urban neighborhoods and midsized projects stand to benefit most from gap financing, because these kinds of projects are often appealing to the public sector and less appealing to conventional lenders. Nearly one-third of the project budget for AF Bornot Dye Works was funded through historic tax credits, PIDC, and Fundrise, because the conventional lender was less sure about the market success of retail development at this location. Public incentive funding and crowdfunding can help address and expand the opportunity for mixed-use development where it may not otherwise be financeable.

Project Information

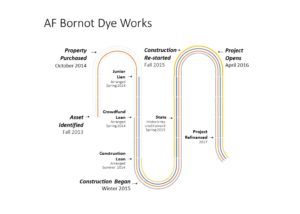

| Development timeline | |

|---|---|

| Planning started | Fall 2013 |

| Construction financing arranged | Summer 2014 |

| Site purchased | October 2014 |

| Retail lease-up | Winter 2014 |

| Construction started | Winter 2015 |

| Residential leasing started | April 2016 |

| Project completed | April 2016 |

| Development cost information | |

|---|---|

| Real estate acquisition costs | $2,465,032 |

| Soft costs | |

| 3% transfer tax | $76,188 |

| Legal expenses | $98,393 |

| Title insurance | $33,848 |

| Insurance | $44,518 |

| Architecture and engineering | $351,895 |

| Environmental reports and remediation | $163,350 |

| Bank inspections | $7,500 |

| Interest reserve (partner equity) | $10,600 |

| Interest reserve (Fundrise, PIDC, bridge loan) | $131,925 |

| Working capital, real estate taxes | $59,255 |

| Historic tax credit costs | $203,642 |

| Bank financing fees | $146,003 |

| Leasing commissions | $119,252 |

| Total soft costs | $1,446,369 |

| Hard costs and contingency | |

| General contractor (guaranteed maximum price) | $6,448,560 |

| Contingency | $110,045 |

| Total hard costs and contingency | $6,558,605 |

| Interest reserve (bank loan) | $260,000 |

| Total project costs | $10,730,006 |

| Financing sources | |

|---|---|

| Senior debt capital sources | |

| BB&T | $6,957,670 |

| Equity capital sources | |

| Sponsor equity | $480,000 |

| Federal historic tax credits | $1,907,336 |

| State historic tax credits | $215,000 |

| Crowdsourced mezzanine loan | $375,000 |

| Public sector capital sources | |

| Philadelphia Industrial Development Corporation (PIDC) loan | $750,000 |

| City of Philadelphia façade grant program | $45,000 |

Format

Deal Profiles

City

Philadelphia

State/Province

PA

Country

USA

Metro Area

Philadelphia

Project Type

Multifamily Rental

Location Type

Other Central City

Land Uses

Fitness Center

Multifamily Rental Housing

Retail

Keywords

Adaptive use

Crowdfunding

Deal profiles

Dealprofiles

Historic preservation

Historic tax credits

Loft apartments

Neighborhood retail center

Site Size

0.55

acres

acres

hectares

Date Started

2013

Date Opened

2016

Website

www.afbornotlofts.com

Project address

1726–1744 Fairmount Avenue

Philadelphia, PA 19130

Developer

MMPartners LLC

Philadelphia, PA

www.mmpartnersllc.com

Architect

Cope Linder Architects

Philadelphia, PA

www.cope-linder.com

General contractor

Axis Construction

King of Prussia, PA

Interviewees

David Waxman, managing partner, MMPartners

David Segal, senior vice president, TriState Capital Bank

Ben Miller, chief executive officer, Fundrise

Principal Author

Payton Chung