Format

Deal Profiles

City

Oklahoma City

State/Province

Oklahoma

Country

USA

Metro Area

Oklahoma City

Project Type

Office Building(s)

Location Type

Other Central City

Land Uses

Office

Retail

Keywords

Community development

Deal Profile

Dealprofiles

Office

Renovation

Retail

Social Equity

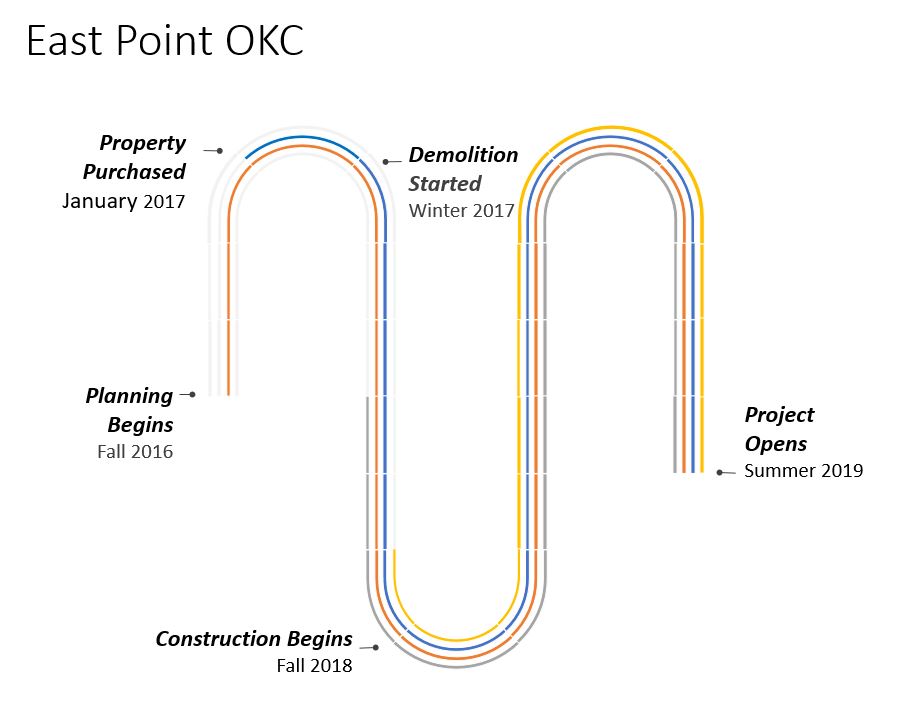

Date Started

2016

Date Opened

2019

The EastPoint Project, when complete, will have 41,202 square feet of renovated single-story retail and office space along a commercial corridor in northeast Oklahoma City. The 18,000 square foot first phase includes 10,000 square feet of medical space and complementary retail. This Deal Profile focuses on how that first phase overcame lenders’ doubts to deliver the first new retail space to a neighborhood in a generation.

The Site and Neighborhood

The EastPoint Project includes the rejuvenation of a series of single-story commercial structures facing Northeast 23rd Street, a retail corridor spanning the northeast quadrant of Oklahoma City. The site is 1.25 miles east of the Oklahoma State Capitol and 2.5 miles northeast of downtown. The first phase renovated a structure west of Rhode Island Avenue, built in 1931 as a highway service station. The second phase renovated a multi-tenant retail building east of Rhode Island Avenue.

The Northeast 23rd corridor was largely built up by the mid-20th century as a commercial artery for subdivisions surrounding the then-new state capitol. Segregation and sprawl led to disinvestment, particularly in the largely African American northeast quadrant. Some local residents have fresh memories of the insensitive urban renewal schemes that displaced African American neighbors from longtime homes in communities like Deep Deuce, closer to downtown OKC.

The Initial Idea

Jonathan Dodson, with partners Ben Sellers and David Wanzer (see previous ULI Entrepreneur Profile), launched Pivot Project in 2014, establishing a record for creative redevelopment and infill around central Oklahoma City. Not long after a Tax Increment Financing (TIF) district was established to spur new investment in northeast Oklahoma City, the Alliance for Economic Development of Oklahoma City, which manages the city’s economic development programs, reached out to Pivot about the largely vacant EastPoint site, then partially under the urban renewal authority’s ownership.

Pivot agreed to take a look, but wanted to have the plan defined by locals rather than by outsiders. Dodson’s first call was to Sandino Thompson, a community development leader he knew who lived nearby. Thompson agreed to help with project strategy in return for an equity stake and fee income. Pivot also committed early on to provide equity stakes for tenants as a way of giving an ownership stake back to neighborhood stakeholders (see Equity below).

Dodson knew that the Oklahoma City Clinic (now Centennial Health) had to leave its longtime home nearby and wanted to stay in northeast Oklahoma City. Many of its customers were state employees, and the site was just down the street from the Capitol complex. Local business groups like NE OKC Renaissance and the Black Chamber of Commerce concurred that health services were lacking in the area, and the clinic would provide a solid anchor for the development

A subsequent phase, financed separately, would renovate another existing building for a complementary mix of retail and other medical services, with a fitness studio as the first tenant. A brightly colored new facade, gathering spaces, and compelling tenant mix of local businesses would bring in customers from within and beyond the neighborhood.

The Idea Evolves

Dodson, who began his career as a lender at a local bank, thought for sure that landing a construction loan for the first phase as a standalone project would be straightforward. After all, they were an experienced sponsor, with city backing, and the clinic’s pre-lease covering the debt service.

Then he started dialing, which opened their eyes up to a world they didn’t know existed.

“I went to over 25 banks, and unequivocally the answer was ‘no’. The honest response was, ‘we don’t lend money to that side of town’,” he says. Other banks cited the lack of comparable new construction, which removed the moral argument, trying to use market tendencies to justify the same reasoning.

Jabee Williams, who is opening a restaurant at EastPoint, put it this way to the Oklahoma Gazette: “If you go to get money from a bank for a house or for a business, you still can’t get it. Not because the bank is saying, ‘I’m racist. We don’t give to black folks,’ but by that point, after those conditions have been set in place for 50 to 60 years, that’s just something you don’t do.”

Negotiations got a little bit further with one bank, where a loan officer said they’d need an outside guarantor before bringing the deal to loan committee. Dodson turned to an acquaintance, a deep-pocketed local developer who agreed to backstop the risk. That bank’s board still vetoed the deal.

Dodson’s last-ditch effort was to a community bank in the affluent suburb of Edmond, which had lent to another Pivot deal a few miles west on 23rd Street: “I was honest with [Citizens Bank of Edmond’s CEO, Jill Castilla]: we’re going to go bankrupt trying to cash flow this deal.” Castilla’s first reaction was to say, “I believe in what you’re doing, and let’s see if we can find a way to make this work.”

Not everyone was thrilled with the news. Dodson called back the clinic’s leadership, which said that the deal had taken too long and that they’d decided to break their lease. Within one day, the Alliance and Dodson convened a boardroom full of civic leaders to urge Centennial to honor its lease. Cathy O’Connor, president and CEO of the Alliance, recalls that it was a show of force to tell Centennial: “We’re all here helping to make this thing successful. The mayor was there, the now-mayor (who was then a state senator), the city manager, the urban renewal commissioners, city council people—I’m not sure we’ve turned out that kind of crowd often, but it worked.”

Financial Overview

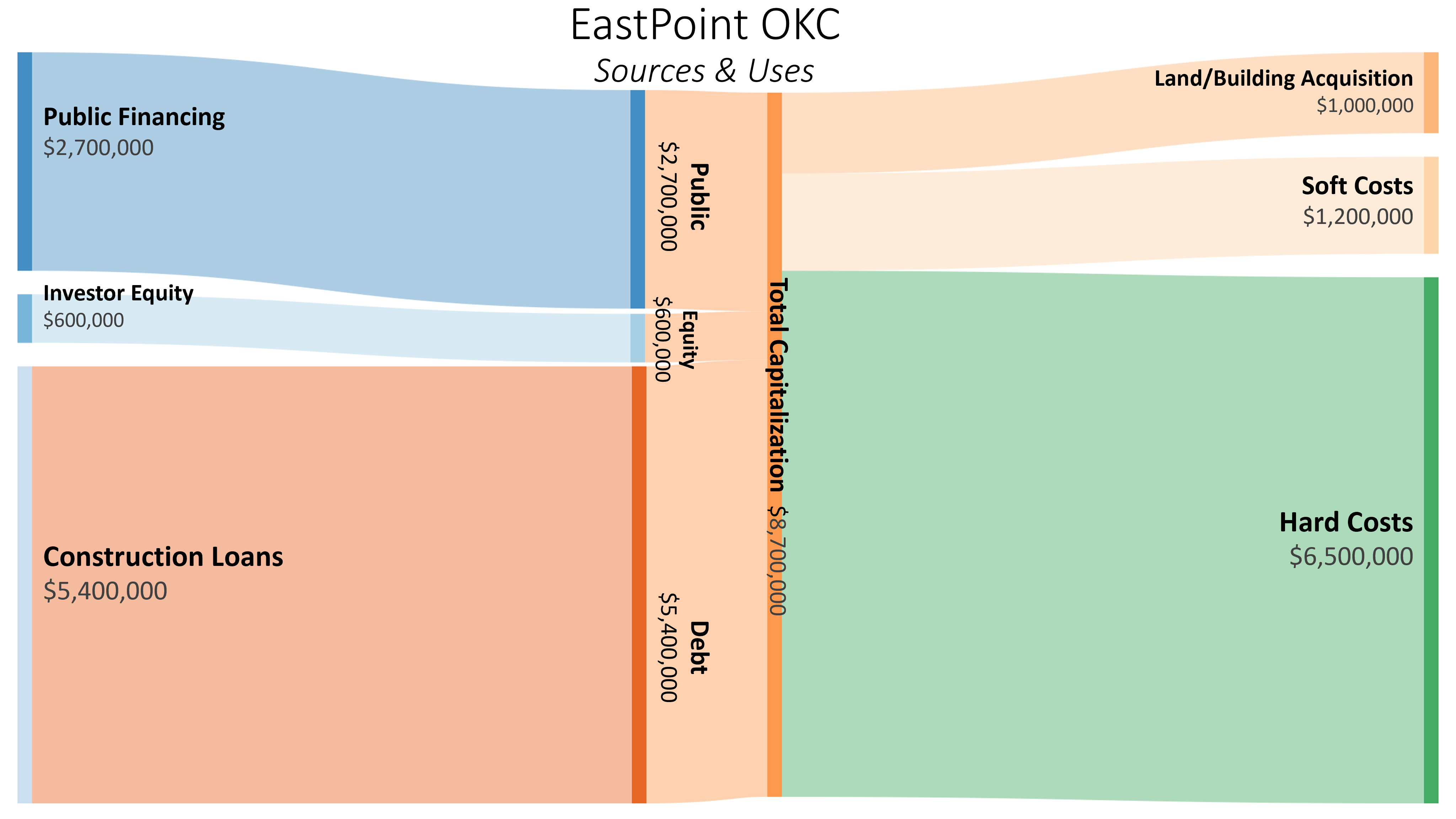

The $8.7 million budget for the two phases was covered by $5.4 million in construction loans, from two community banks and a $600,000 equity contribution from an equity investor. About 27 percent of the project budget was from TIF funds.

Public Financing

It was clear that, besides the site, part of which was procured through a Request for Proposals process, TIF funds would be needed to see the project through.” It was pretty apparent that this project was just way too risky without that kind of commitment from the city,” says O’Connor.

The $1.3 million TIF allocation for the first phase is split between a $600,000 soft loan (gradually forgiven over time) and a $700,000 predevelopment grant. O’Connor points out that “typically, we don’t do that. Instead, we pay it out over time,” as revenues trickle into the TIF, and that it was unusual to write a check for a project that “does not generate enough increment to pay back the allocation.” Because the young TIF district had little saved in its accounts, the City borrowed money internally.

The upfront TIF funds were politically contentious, and the local partners that Pivot Project involved early on turned out to be crucial in the process. The allocation ultimately kept the project going, despite high predevelopment costs and the interminable delay in getting a construction loan. “We also used the TIF to provide additional tenant improvements and reduce the rent—we’re charging 25% below what we would do two miles away, and doing six times the TI to build out the space,” Dodson says. The TIF allocation came with certain provisions and requirements including a clawback provision if the project is sold within ten years.

Equity

In an unusual move, Pivot has granted an equity stake in the project entity to the project’s tenants. “I couldn’t imagine developing this, and not having tenants share in the upside,” he says. Their 15 percent ownership means “we’re giving up the majority of the value, but that was created by the people who took the risk” of opening businesses and creating the site’s value. The equity, divided as a percentage of the space occupied, includes a

share of the project’s cash flow over the city’s 10-year lockup period. After that 10 years, provided the lease has not been defaulted on, the ownership stake can be sold.

“We hadn’t seen it done before,” Dodson says, “but we’d seen areas get gentrified. We wanted to figure out how to develop thoughtfully without forcing out the value creators” and the small, local businesses pour so much time and effort into creating retail destinations. The offer of an equity stake did attract some businesses, who might have found cheaper options elsewhere – but for other tenants, the speculative and far-off returns on equity were difficult to comprehend.

A conventional equity investment was made by a local physician who, Dodson says, “had a heart for what we were doing… He could have put his money to better work, but we were honest about it with him that this is a really difficult project, but it will change a community. We’re grateful that he was willing to do that.” Still, Dodson doubts he can find many other investors with a similar commitment. He also doubts there are many other private developers willing to make a similar time commitment to make sure this kind of deal will be done correctly.

Debt Underwriting

Castilla proudly points out that Citizens Bank of Edmond is “not fixated on annual profitability, but long-term sustainability – not just for the bank, but the community we serve.” Part of that, she continues, is forging “great investment partnerships with leaders throughout the metro area who are putting their capital at risk, so we can create economic vitality and sustenance for our communities.”

A few years ago, Citizens had lent to Pivot when it took on the rehabilitation of a large theater on Northwest 23rd Street. “We loved [the Tower Theater] project,” Castilla says. “And were able to come in at a time when they really needed a partner, to hold hands and jump off the cliff together. Luckily, there was water at the bottom of the cliff.”

The location on Northeast 23rd Street was not necessarily a tougher sell to Castilla, who cites “our openness to listening, and then buying into the vision of where the development was going.” ”We quickly found out that other banks had passed on it,” she says – “but we were able to make sure that the credit was underwritten correctly to mitigate the risk,” noting the triple backstop: a credit tenant’s lease guarantee, the guarantor, and “also a wonderful developer who can leverage not only assets but also expertise and passion.”

The key to successfully underwriting here was to tailor the loan to the particulars of this deal: to “approach each deal on its own merits, and instill covenants and attributes for each loan to ensure that we’re being prudent and flexible,” Castilla says. In this particular case, that meant “evaluating the deal on its merits, and looking at those contributing their credit to the deal.” For instance, other banks had trepidation about how the site would appraise, but Castilla says that ultimately, “the appraisal was not an issue. We poked around even before the appraisal was ordered” and found comparables, regardless of the geography.

Dodson says that once Citizens gave the project their imprimatur, a construction loan for the second phase was much easier to secure.

Lessons Learned

Impact investing. Dodson shopped the loan around to local foundations, to no avail; in his words, their response was “you don’t make enough money for our [endowment] side, but you make money—so we can’t give you any [grant] money.” He’d like to see more investors realize that the two intersect.

The project has certainly made an impact in the public consciousness, though, garnering unprecedented local attention for its mission. Dodson says “there are a lot of bigger projects in the city, but not any trying to take on gentrification and in a place that hadn’t had any development in 40 years.”

Increments. O’Connor appreciates that the project was of a small scale size that it reduced the risk, pointing to bigger proposals in Northeast that have taken even longer

to get going. She points out, “sometimes these smaller projects are easier to do, get financed, and better reflect the character of the community they’re in… and still help to serve as a catalyst for other investment.”

In a sense, Dodson’s instinct to finance the phases separately did pay off. Once the right lender realized that a construction loan on the first phase could be adequately backstopped, that loan signaled to other lenders that it would be okay to proceed with subsequent phases.

Access to capital. Dodson is most struck by how completely cut off from capital northeast Oklahoma City was; “it’s not that [local residents] didn’t know what to do with money, but because others pulled the money out of the market,” he says.

He was also struck by the need to invest in human capital, as well. Pivot’s partners found themselves coaching would-be tenants in paperwork, including filing for permits. Several spaces have had to be re-leased multiple times, as various ideas fell through, but that patience also resulted in a more compelling tenant mix.

Restoring access to capital pays off over time, but it requires vision and leadership. Castilla points out that “one of the purposes of a community bank isn’t just to finance a project yourself, it’s to provide leadership that creates economic vitality” all around. She sees investments like EastPoint as integral to the bank’s long term: “We have survived 119 years not so much by rich financial capital, but by strong social capital.”

Format

Deal Profiles

City

Oklahoma City

State/Province

Oklahoma

Country

USA

Metro Area

Oklahoma City

Project Type

Office Building(s)

Location Type

Other Central City

Land Uses

Office

Retail

Keywords

Community development

Deal Profile

Dealprofiles

Office

Renovation

Retail

Social Equity

Date Started

2016

Date Opened

2019

Project Information

Website

https://pivotproject.com/project/ne-23rd-corridor/

Video

https://vimeo.com/355116802

Address

1720 Northeast 23rd Street

Oklahoma City, OK

Developer

Pivot Project

Architect

Miles Associates (west building)

General Contractor

Lingo Construction

Tenants

Centennial Health

Intentional Fitness

Oklahomans for Criminal Justice Reform

Kindred Spirits

(optometrist)

(art gallery)

Ground House Burger

Interviewees

Jonathan Dodson

Co-founder

Pivot Project

Cathy O'Connor

Alliance for Economic Development of Oklahoma City

Jill Castilla

CEO

Citizens Bank of Edmond

Matt Scantlin

Citizen Bank of Edmond

Principal Author

Payton Chung

Contributing Authors

Jacob Behrmann

Clayton Daneker