Format

Full

City

Los Angeles

State/Province

CA

Country

USA

Metro Area

Los Angeles

Project Type

Mixed Use

Location Type

Other Central City

Land Uses

Arts Center

Multifamily Rental Housing

Office

Plaza

Restaurant

Retail

Structured Parking

Transportation Use

Underground Parking

Keywords

Affordable housing

Air rights

Art center

Arts-oriented development

Low-income housing

Mixed-income housing

Mixed-use development

Neighborhood retail center

Outdoor events

pedestrian streets

Public-private partnership

Transit-oriented development

Site Size

4.03

acres

acres

hectares

Date Started

2005

Date Opened

2014

A bright white “side-scraper” stretches three-tenths of a mile along the eastern edge of downtown Los Angeles, sandwiched between railroad yards and the river on one side and the city’s burgeoning loft district on the other. This structure is One Santa Fe, whose 510,000 square feet of space includes 438 apartments (88 of which are affordable units), as well as 78,620 square feet of retail and office space. The development, located on a narrow parking lot leased from a transit authority, was built using $165 million in public and private housing and commercial financing. Surrounding One Santa Fe’s internal pedestrian promenade is an eclectic mix of retailers, including both local convenience businesses and regional specialty shops that complement the neighborhood’s artistic and creative energy.

[ Introduction and Neighborhood Context | The Site and the Idea | Approval Process | Development Finance | Planning and Design | Performance, Marketing, and Management | Observations and Lessons Learned | Project Information ]

Introduction and Neighborhood Context

In a city famed for creating fantasies, plain-spoken street names like Traction, Factory, Produce, and Wholesale set the Arts District apart. Its sturdy lofts sprang up to mill inbound lumber, box up truckloads of outbound oranges, or mix soft drinks for the booming city.

The lifeblood of these factories was the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe (AT&SF) Railroad, whose tracks alongside the Los Angeles River sparked a property boom after their completion in 1887. In 1893, the AT&SF completed on One Santa Fe’s site the La Grande station, whose outlandish architecture made it a favored backdrop for films starring the likes of Laurel and Hardy, the Little Rascals, and Fred Astaire until it was torn down in 1946. Across the street from its yard, the AT&SF built a quarter-mile-long freight depot where inbound trains could unload directly onto up to 120 waiting trucks.

A shift to more horizontal industrial facilities along highways left the area derelict and ripe for resettlement by the 1970s, when artists first set up studios in empty industrial buildings. Following the adoption of an artist-in-residence (AIR) ordinance in 1982, a few thousand residents slowly established themselves amid the brick lofts, separated from downtown’s glittering skyline by blocks of wholesalers and the city’s infamous Skid Row. A few businesses followed, such as coffee shops and punk music clubs, but the area was best known as a convenient backdrop for Hollywood scenes depicting urban decay and abandonment: the dry riverbed and the Sixth Street Bridge behind One Santa Fe is the setting for numerous cinematic drag races, including the one in Grease.

Institutions and infrastructure gradually followed those first businesses. The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, opened in 1983 in what was a warehouse between the Arts District and Little Tokyo, and now anchors a cluster of 20 contemporary art galleries and exhibition spaces. In 2000, the Southern California Institute of Architecture (SCI-Arc) renovated the freight depot across the street, bringing 500 students with rigorous schedules to the desolate edge of downtown.

Public investment in Los Angeles’s long-neglected urban landscape also drew new attention to the area—notably the adoption of the decades-long Los Angeles River Revitalization Master Plan in 2007, which seeks to reinvent the oft-ignored flood channel just to the east, and the 2009 opening of the Metro Gold Line’s Little Tokyo/Arts District light-rail station five blocks to the west. (A new tunnel is being built beneath downtown to link that station to Metro’s other light-rail lines.)

A broader Adaptive Reuse Ordinance (ARO), based on the AIR ordinance, was passed in 1999. Together with the housing boom and growing interest in urban living, the ARO touched off a surge of office-to-residential conversions (see Old Bank District case study, casestudies.uli.org/old-bank-district-4) that redefined downtown L.A. as one of the country’s trendiest neighborhoods. The boom reached the Arts District in the mid-2000s, and the number of residences in the area doubled as loft condominiums and small infill apartments were built. Restaurants soon followed, first at the fringes of century-old Little Tokyo and later within the Arts District. Yet this “great neighborhood had a tattered, frayed edge along the train yard,” recalls Charles Cowley, president of Cowley Real Estate Partners, one of the developers of One Santa Fe.

Back to top

The Site and the Idea

The One Santa Fe site stretches for nearly one-third of a mile along South Santa Fe Avenue, between First and Fourth streets, about 0.7 miles southeast of City Hall. It sits at the western verge of what were AT&SF railyards along the west side of the Los Angeles River, which were sold in 1984 to a newly created public transit agency. The Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority (Metro) later inherited the 50-acre riverside railyards, repurposing them in 1993 for use in servicing and storing subway cars.

Construction difficulties led Los Angeles County voters to suspend subway construction in 1998 and shift Metro’s resources to surface-running light rail and bus rapid transit. The vast Santa Fe yards seemed too large for Metro’s small subway operation, so in 2004 the agency invited proposals from developers to lease and develop a surplus parking lot at the yard’s inland boundary.

For Metro, developing the site offered multiple upsides beyond the rent checks. A new building there would act as a sound barrier for the rail operations. In 2000, Metro staff floated the relatively low-cost idea of building a new rail station within the existing yards; after all, the trains already had to go there. A new building right in front of the yards could both bring new riders and serve as a monumental station entry, built and maintained at developer expense.

Metro could also stipulate lease conditions that would leave its options open; not only did Metro require replacement employee parking within the garage at below-market rates, but it even retained the right to demand that the building be demolished and the site revert to being vacant at the end of the lease should rail operations need the space then. Its lease also holds Metro blameless for nuisances caused by its railyard and requires that the building mitigate noise.

Nick Patasouras, president of Polis Builders Ltd., who is also a longtime civic leader, scrutinized a list of Metro properties made available for redevelopment. Among those sites was the Santa Fe yards; he had Michael Maltzan Architecture draw up some schemes for how buildings could fit there. The residential upswing downtown indicated that a market could exist for rental housing on the site, perhaps in more conventional spaces than could be found in the cavernous lofts nearby. At the right price point, the rentals could appeal to SCI-Arc students—and a mid-rise, stick-over-podium building could meet that price. In later negotiations, Metro staff suggested that a plaza and retail space be included, which could fill a niche in the growing community.

Patasouras brought the idea to the McGregor Company, which joined the effort. Later, Cowley, then senior vice president of McGregor, shepherded the project through approvals while at McGregor and subsequently under his own firm, Cowley Real Estate Partners.

Back to top

Approval Process

The parcel had an absurd shape: on the north end, it was a 35-foot-wide half aisle of parking squeezed between a repair workshop and a fence, and on the south it was a wider wedge. To make it a usable 65 feet deep required some ingenuity. Two-lane Santa Fe Avenue was 88 feet from curb to curb, a width once required so that trucks could back up to loading docks, but later only invited drag racers.

With local city councilwoman Jan Perry’s help, the developer petitioned the city Department of Transportation and city council to narrow the street through a “functional reclassification.” That succeeded in vacating the city’s easement on 25 feet of right-of-way, returning it to Metro, which could then include the property in the lease. Another five feet of width was gained by leasing air rights over the street right-of-way.

The resulting 65-foot-wide parcel was now just wide enough to accommodate an apartment building with a double-loaded corridor, and the resulting 54-foot-wide street was more appropriate as a collector street in an urban residential neighborhood.

Another complication that required attention from Metro’s lawyers was the fact the site’s title was encumbered by a 2001 leaseback arrangement with Agilent Technologies, via a subsequently discontinued tax shelter through which the transit authority sold its depreciation rights to a private company.

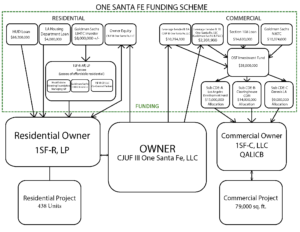

In 2011, the ground lease was restructured to meet U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) requirements, particularly to reflect the separation of the project into multiple legal entities. The final lease term was for 81 years, with a base rent set at $525,150, plus a percentage of commercial rent, and a schedule of increases greater than the consumer price index.

The Arts District retained its industrial zoning at the time; most residential development had been permitted under the AIR ordinance rather than through rezoning. The railyard was zoned as a “public facility,” so building One Santa Fe required council approval both to amend the general plan map designation to “regional commercial” and to then rezone the site to C2-2D—a commercial zoning classification that required no additional setbacks. The development also required a separate site plan review.

Getting neighbors on board with such a high-profile development in notoriously prickly L.A. required some finesse. Cowley recalls approaching neighbors to “tell us what we can do, because we want to be good neighbors.”

One realization was how character defining the retail spaces would be for the building and the area because they would be some of the first purpose-built retail spaces in the neighborhood. Early on, the team committed to finding a grocer.

Another bonus for the neighborhood was the dedication of a 5,000-square-foot, street-facing retail space as an art center, the space leased at a nominal rate to a local nonprofit organization. While this move did not eliminate all the complaints—several neighborhood organizations remained opposed to the development—it did move sentiment enough to help with approvals.

Back to top

Development Finance

The financial crisis upended the financial structure of One Santa Fe. Although the project was approved as a market-rate building, conventional banks and equity investors were a hard sell in this location even before the market collapsed—and certainly afterward. Ultimately, the team found that community development–oriented financing remained standing during the crisis, and reoriented the project to meet those requirements.

“Securing a construction loan was proving to be somewhere between extremely difficult and impossible,” William McGregor, president of the McGregor Company, told Multifamily Executive. Given the paucity of private construction lending, the developers investigated several sources of public financing. An application for a low-interest loan disbursed from a $590 million pool established in 2006 by California’s Proposition 1C (see ULI case study of St. Joseph’s Campus, casestudies.uli.org/st-josephs-campus) came up just short of qualifying.

Multifamily mortgage revenue bonds, which generate 4 percent low-income housing tax credits for additional equity, seemed like a good match for a project of this size and scope—especially since the U.S. Treasury Department had just pre-funded $580 million in California Housing Finance Agency bonds in January 2010 under its New Issue Bond Program (NIBP), aimed at stabilizing the municipal bond market. The catch was that the project would have to set aside 20 percent of its units as affordable at 50 percent of the area median income (AMI). “The NOI [net operating income] that was given up was significant. However, such a sacrifice was required in order to get the project built,” says Cowley.

Initially, HUD’s regional office was operating under an interim director, and staff members were reticent regarding taking on such a high-profile risk without some sign from above. A new regional director, Kelly Boyer, proved to be the project’s champion, says Cowley. “She could see the vision—that this could be a poster child for what HUD could do.”

HUD was still circumspect about the market demand for so many new apartments and demanded intensive market analysis before committing to the deal. This proved far more complex than usual; as Cowley points out, a “classic appraiser would draw concentric circles, but we had to get outside of that box.” Analysis of a one-mile radius around the project site would show Skid Row on the west and working-class Boyle Heights on the east, completely overlooking the Arts District sandwiched between the two.

Instead, the team commissioned a detailed market analysis that zoomed in on the Arts District’s 2,975 new-construction residences, the 13,000 market-rate rental units around downtown, and downtown’s economic resilience relative to the rest of the region.

“We went door to door making a map of every building, how many people lived there, how many businesses. . . . We hired a survey group to find out where people are moving from. We knew that people were moving from Hollywood, but until then we couldn’t prove it,” says Cowley. It turned out that 70 percent of the residents had moved from outside the center city, with 17 percent moving from the increasingly pricey Westside and 12 percent coming from out of state.

With the market study in hand, HUD decided in September 2010 to proceed with the $86.2 million loan, as well as credit enhancement through the Federal Housing Administration’s 221(d)(4) mortgage insurance program. The bond financing had a 34-year maturity, and a four-year interest-only construction period. One downside of the NIBP was negative arbitrage—paying interest on $86.2 million in bond proceeds that have not yet been spent but must sit in a low-yielding savings account.

An additional $4 million soft loan was made from the city’s housing trust fund. This required lower rents on the affordable units: two-thirds of them would be affordable at 40 percent of AMI.

Accepting a HUD loan also required revamping the project’s legal structure to work around HUD’s tight limit on commercial floor space. That required separate legal entities to own the affordable housing, market-rate housing, and commercial portions. The site was re-subdivided with a horizontal datum separating the ground floor from the upper floors, and new leases were drawn up for both new parcels. The ground lease also had to be rewritten to meet various HUD terms.

Once the commercial space had been separated, it was possible to finance that portion with a $14.6 million Section 108 loan from the city’s Community Development Department under a program that allows cities to loan federal Community Development Block Grant funds. That loan leveraged New Markets Tax Credits, which were ultimately sourced through three community development entities: Los Angeles Development Fund, Clearinghouse CDFI, and Genesis LA.

While the debt financing was coming together, the project’s equity stack also had to be rearranged. After the ground lease was secured, the developer sought a joint venture partner for equity via a broker, and Goldman Sachs Urban Investment Group joined the venture in 2007. Shortly thereafter, the financial crisis hit; Goldman’s cost of capital sharply increased and its risk tolerance decreased. The team cut back on spending and in June 2009 stopped design work when the construction documents were 80 percent complete.

Goldman backed out in late 2010, kicking off a search for a new equity partner before the site’s zoning approval lapsed. (Goldman did remain in the project to syndicate the project’s tax credits.) After a brief search, the Canyon-Johnson Urban Funds (see ULI case study of Harper Court, casestudies.uli.org/harper-court) emerged as the frontrunner in 2011. As a locally based company, founded in 1998 expressly to focus on inner-city areas that conventional banks had neglected, Canyon-Johnson was not dissuaded by the edgy surroundings.

“It was touch and go until the very last week,” says Cowley. The bond financing absolutely had to close by the end of 2011 (the last of several extensions made to the NIBP), and ultimately did so on December 22.

Back to top

Planning and Design

One Santa Fe’s sheer size and its location at the outer edge of downtown guaranteed that it would become an instant landmark in the cityscape. Its bold design embraces the site’s prominence, drawing from both the site’s unusual dimensions as well as the angular, flowing forms of the railyards and river alongside it. The architecture has landed it on the cover of Architectural Record and the Los Angeles Times Sunday Styles section.

One Santa Fe consists of two long mixed-use structures: one hugs the western Santa Fe Avenue boundary for the northern two-thirds of the site’s length, and the other angles northeast to southwest, following the eastern edge of the wedge at the site’s south. Between the two is a triangular pedestrian plaza lined with cafés, which narrows to a paseo as it wedges between the two buildings. The paseo widens at its northern end into a broad open space at the complex’s center; the western building leaps like a bridge over a 300-foot-wide, 35-foot-high void where the plaza opens to the sidewalk. The east building has a narrower three-story cutout; although screened in at this time, it can accommodate a future pedestrian bridge over the railyard to a proposed Metro station and riverwalks to the east.

Architect Michael Maltzan says that the “incredibly long and generally thin site, characteristic of a neighborhood [with] long, thin pieces of infrastructure,” inspired an approach that was “not so much trying to recall rail, but rather the history of movement on that site,” as well as its surroundings, including the river, the rails alongside it, and the long road bridges spanning both.

Maltzan was also interested in how the building could help guide the historically sprawling city’s approach to higher density. “Taking on the issue of emerging density in Los Angeles was a real ambition from the beginning,” he told Form magazine.

At the same time, Maltzan says he understands that “one of the primary expectations that many people have about living in a climate and culture like L.A. is that you have access to outdoor space. That is, in many ways, in conflict with creating models of denser residential structures, where there’s very little individual outdoor space.” One Santa Fe was one step to “explore what that right balance is between outdoor space for individuals and for the community.”

“We looked to create layers of experience at different scales” within the large building, Maltzan says, beginning by shaping the building’s massing. Pushing the building out to the edges of the site wrapped the residences around a communal open space at the center of the site, and reinforced what Maltzan terms “a continuous and traditional street wall” for the mixed-use street frontage.

Yet the street wall’s permeability makes it more of a portal than a boundary to the neighborhood. Whereas “most apartment buildings are walled-off compounds,” Cowley says, “One Santa Fe turns that paradigm on its head: as it delaminates, it pulls away from that right of way so that you’re able to go into that interior paseo” and visit the retailers.

“Creating as lively and as complex a version of urbanism in the building as we could” was a priority for Maltzan. At eye level, that means that “many scales, layers, and particular moments [are] woven throughout the building, [which] should create real moments of connection” for residents and visitors. These include the structural bridge over the plaza, geometric planting beds that define different paths along the paseo, smaller openings between the sidewalk and paseo, and gentle zigzags within the building corridors.

The plaza is bookended at the north by a low, three-story building that hides a circular parking ramp. At grade, this houses retailers, including the grocery and a restaurant; above is a residential amenity deck with a swimming pool, grills, a fitness center, an indoor resident lounge with a community kitchen, and a film-screening amphitheater tucked beneath the bridge but atop a restaurant. (Some neighborhood wags jokingly refer to the building as the “cruise ship,” pointing to the pool atop a long white structure.) An additional amenity area, with a hot tub, a grill, and unobstructed city views, is hidden in a notch within the west building that overlooks the intersection with Second Street.

The building’s tremendously long frontages, both along the street and the plaza, create numerous wide-but-shallow retail spaces whose long window lines are a sharp contrast with the deep loft spaces found elsewhere in the neighborhood.

The structure is of conventional podium construction, with four to five floors of stick-built apartments over a concrete podium of retail space, offices, and parking. Maltzan says there is “an expectation of uniformity in stick-built, but there’s still a reasonable amount of sculpting of the building that you are able to do.” Hybridizing the construction technique can “take advantage of other structural methods to create as expressive a building as possible.” The circular concrete parking ramps were exposed at the north end to punctuate the building’s rectangular mass, while a steel truss carries the west building over its bridge portion. Metal shades protrude from the facade to add depth and shadow while also screening harsh southern sun.

One floor of below-grade parking for residents underlies the entire site; any further excavation could have undermined railroad warehouses that sit just behind the property. The central plaza typically doubles as two aisles of parking for retailers, but is regularly closed off for events. Metro’s offices sit below two levels of above-ground agency parking, which also lifts the apartments at that end of the building above the roofline of an adjacent warehouse.

Construction next to an active subway-train yard added its own challenges. Relocating numerous utilities, including two natural gas distribution lines, high-voltage power lines, an electrical substation, and telecommunications lines, took eight months. Ongoing site preparation work contributed to a decision to construct the building in several phases, from south to north.

Both Cowley and Maltzan note that value engineering dulled the interior finishes. Maltzan points to the landscaping and unit interiors, Cowley to the residential lobbies. On the other hand, the project did benefit from some economies of scale. Cowley, disappointed with the quality of touch points like plumbing fixtures and flooring affordable within the specified budget, received approval from the partners to circumvent suppliers and directly source from overseas suppliers higher-quality products that met the budget.

Back to top

Performance, Marketing, and Management

One Santa Fe has helped catalyze the Arts District’s emergence as the hottest submarket in downtown L.A., which is seeing its largest building boom in a century. Its new units were the first new product delivered downtown after the recession and proved the area’s potential to absorb large-scale development. While “it was difficult for us to convince institutional investors that this was the right place to be, and not until 2012 did other institutions start to come into the area, now the area is replete with projects under construction, in design, in review,” says Cowley—even high-rises designed by superstar architects.

Many of these projects are copying One Santa Fe’s pedestrian paseos and curated retail offerings—but combined with uses once unthinkable in the area, like corporate offices, five-star hotels, and haute couture. The transformation has drawn attention from the region’s all-important entertainment industry, along with media from the Financial Times to Variety. The long-planned subway station within the Santa Fe yards is now fully funded, though its final location has yet to be determined.

One Santa Fe was sold in June 2016 to Berkshire Group, a Boston-based privately held real estate investment management company that owns or manages more than 24,000 apartment units in 20 major markets. Emily Watson, senior vice president of Berkshire Communities, the company’s operations division, says the property matched the company’s focus on transit-oriented, “core infill locations with walkability and a commitment to sustainability.” The property has exceeded expectations and is on track with Berkshire’s underwriting, says Watson. Since entering the market with One Santa Fe, the company has purchased two additional communities in downtown L.A.

Residential. The project achieved 93 percent occupancy in 2016, “and we were comfortable with that, but we’re at 97 percent today,” says Watson. “It’s easy to sell,” largely due to its convenient location within “the most walkable part of downtown,” she says, with daily essentials like groceries within walking distance, plus services like an on-site concierge, delivery lockers, and the amenity deck. Distinctive amenities also include electric vehicle chargers, on-site car-sharing vehicles, and a fleet of 50 bicycles that can be checked out for daily use by residents.

Studio apartments leased up quickly, thanks in part to the entry-level price points enabled by small unit sizes (down to 340 square feet) and an initial influx of students. The large, multistory townhouse-style units in the bridge “have been tougher to find the right equilibrium on the price level,” says Watson. As the resident mix expands to include more people drawn to the location, the larger units have become easier to lease.

The building’s long and thin layout ensures views in every direction. The western skyline views are the most popular, but other apartments look out over the paseo, the railyards, the river, and the San Gabriel Mountains.

The developers supported the effort by the city’s Cultural Affairs Department to land a National Endowment for the Arts grant for an affordable artist housing initiative during lease-up. In order to help keep artists in the Arts District, workshops were held to help local residents without conventional incomes understand the documentation they would need to apply for the income-restricted units.

Commercial. The ground-floor space at the quieter north end of the site was pre-leased to Metro for railroad training and operations offices through an amendment to the ground lease. The lease helped the developer meet a commercial pre-lease obligation related to its city financing and comes at no cash cost to Metro because the rent is simply deducted from the future ground lease payments. An influx of capital funds around this time meant that Metro’s rail operations were again growing, and the railyard was a logical location for that space.

For the retail space at the project’s heart, Cowley says he “very much wanted retail tenancy to be interesting and evoke the neighborhood.” The project’s first retail broker “didn’t understand the neighborhood,” he says, and “brought us a letter of intent from Starbucks. I love Starbucks, but it’s not a tenant we could have at One Santa Fe. The neighborhood would begin protesting! We had to find somebody who’s more creative-minded.”

A business partner mentioned recent consulting done on Platform, a then-proposed commercial development in Culver City that InStyle dubbed an “architectural wonderland and futuristic fashion hub.” Runyon Group, Platform’s young developers, had already pre-leased half the space to Michelin-starred chefs and cutting-edge boutiques—despite a location surrounded by tire shops and warehouses used for heating and air conditioning equipment.

“People thought we were crazy to bring these high-profile brands from all over the world to . . . a run-down 1960s used car dealership,” Runyon cofounder David Fishbein told Vanity Fair in an interview. Says Cowley, “We’d never heard of them before, but thought, ‘Wow, we have got to talk to him.’” He describes Fishbein as being “like an Antiques Roadshow expert, except for hip retail: he can tell you the backstory and provenance of everything—hundreds of restaurants and retailers.” The team went back out to market with a slick look book.

The result has been an eclectic mix of small businesses, and Cowley says he is “incredibly delighted with how the mix of tenants has turned out.” Many of the shops are destination retailers that have found a loyal following elsewhere in the region or nation and were looking to expand into the booming downtown. Others provide neighboring residents with convenient services, making the paseo what Michael Murillo, on-site leasing director for Berkshire Communities, calls “the base camp of the Arts District.”

The grocery anchor is Grow, the second location of a Manhattan Beach, California–based store, which devotes almost half its 5,300 square feet to produce, as well as offers deli, bulk-food, and beer/wine departments. Six other casual eateries have opened at One Santa Fe, offering all-day dining that draws on the wide assortment of dining concepts that have flowered across Los Angeles.

Two shops selling books and related art came to One Santa Fe from opposite ends of the metropolitan area: A Shop Called Quest branched out from the college town of Redlands in the eastern suburbs, while Hennessey + Ingalls relocated its two Westside stores to a site directly across from SCI-Arc’s front door. Several boutiques offering tastefully modern apparel, home decor, and cosmetics round out the soft-goods assortment.

Berkshire “bought into the original developers’ vision” for the retail space, says Watson. While “we’d love to be 100 percent occupied on the retail, finding the right mix for our residents and community is more important to us,” she says. Murillo echoes that the team “did a really good job of curating the tenants, and the residents absolutely love the convenience of walking downstairs” to everyday services.

One Santa Fe has a far larger commercial component than any other Berkshire property. Watson says, “outsourcing the management and leasing gave us a subject-matter expertise in house that we would not have had.” Having a separate management contract creates “a go-to for the retail tenants,” she says. “Having someone who’s not distracted with residents day to day helps to focus the on-site team on the residents and creates value for tenants.”

Marketing and management. Watson says online advertising was used “at the beginning, when we didn’t know what to expect. . . . Once we realized that the Arts District itself really drives the traffic, we pulled off from those campaigns because we don’t need it.” Instead, marketing has pivoted to events held throughout the year, and, Watson says, “we haven’t had to do much in terms of marketing besides the events” and related social media promotion via Facebook and Instagram.

The project sought from the outset to incorporate public art throughout the site, and this has proved to be an unexpected boon in the social media era. In image-conscious Los Angeles, and especially within a neighborhood long known for its street art, a particularly photogenic selfie backdrop can prove irresistible—and a sandwich-board sign outside One Santa Fe promises “Instagram worthy photo opportunities” to passersby. To keep the visual offerings fresh and buzz-worthy, One Santa Fe has hosted a Secret Walls event—a crowd-judged live competition among mural painters described as “the Fight Club of the street art scene.”

A monthly Odd Nights market, coordinated by a local operator of pop-up bazaars, brings craft vendors and food trucks to the paseo on the same night as the neighborhood’s monthly gallery walk. Eighty percent of residents surveyed said they attended the market; Murillo says it “created a greater sense of community and definitely helped cement us within the Arts District” as a retail destination.

Retailers also frequently host events in the open spaces, from weekly comic-book release nights and fashion trunk shows to cosponsored public movie nights in the amphitheater. In Los Angeles, filming and signage rights contribute an appreciable secondary income stream to the project, as well as increased visibility.

Watson notes that management of such a complex project is helped by “putting people in place to buffer” different users, like the retail manager or the parking attendants. Frequent tenant surveys and meetings with on-site staff also identify successes and concerns early on.

Back to top

Observations and Lessons Learned

“This is the most complex, multilayered transaction we’ve ever been involved in,” says Cowley, requiring tremendous persistence amid “all of the drag of legal fees.” Negotiations began more than eight years before groundbreaking and involved countless stakeholders. Yet the persistence also paid off with regard to the market cycle. “Our timing was horrible to start off with; however, because we were able to ride out the recession, our timing became much improved,” recalls Cowley.

Flexibility also paid off, especially with regard to restructuring the financing. Without the switch to public financing, the project would not have been able to proceed, much less deliver into a market upswing. Yet once the first public financing was secured and commitments made for affordability and job creation, it made sense to pursue other financing sources. Recognizing the challenges inherent with projects like this, Metro now requires its joint development projects to include affordable units, and backs up that requirement with a new Transit Oriented Communities Loan Program.

A package of community benefits not only convinced neighbors of the project’s value, but also adds value to the project. Foremost among those amenities are the distinctive and convenient on-site retail offerings.

“The renter of choice has a very busy lifestyle,” says Watson, and locations that maximize convenience have an inherent advantage. “Even when their life changes, there’s enough glue to tie them to that location because it makes sense for their lifestyle,” she says.

The arts center at the site’s southern end has yet to open, due to a few false starts with finding the right operating partner. After engaging a consultant to help lease the space, Watson is confident that it will draw new audiences and complement the area’s other arts venues.

The arts center will add to the variety of artistic and creative experiences that have proved key to marketing One Santa Fe. Watson says that in retrospect she “would not have spent as much up front on marketing. Instead, we should have saved those dollars and relied on events” that let people experience the site’s remarkable offerings on their own terms.

A keen understanding of market niches has been critical to One Santa Fe’s initial and continued success. Convincing lenders that the Arts District could support a project of this size required a deep understanding of its peculiar geography and strengths. The building’s novel architecture and amenities are not for everyone, but a place like the Arts District appeals to residents who appreciate bold statements. Watson says she has learned “not to be afraid of these iconic assets. Instead, embrace it and be able to leverage their unique value.”

Project Information

| Timeline | |

|---|---|

| Exclusive negotiation agreement with Metro signed | September 2004 |

| Joint development agreement and lease terms approved by Metro board | November 2005 |

| Goldman Sachs joined joint venture | March 2007 |

| HUD loan gained preliminary approval | September 2010 |

| Canyon-Johnson Funds joined joint venture | July 2011 |

| Ground leases executed and construction loan closed | December 2011 |

| Construction started | January 2012 |

| Phase I opened | September 2014 |

| Phase II opened | October 2014 |

| Phase III opened | December 2014 |

| Final certificate of occupancy | March 2015 |

| Berkshire Communities purchased property | May 2016 |

| Land uses | Sq ft |

|---|---|

| Building footprint (including underground parking) | 175,000 |

| Gross floor area | 510,000 |

| Open space within site | 53,000 |

| Total site area | 175,648 |

| Parking | |

|---|---|

| Total parking | 802 spaces |

| Retail dedicated parking | 85 spaces |

| Residential dedicated parking | 521 spaces |

| Parking spaces per apartment | 1.19 |

| Project costs | |

|---|---|

| Hard and soft costs | $165,000,000 |

| Public capital sources | |

|---|---|

| Residential | |

| California Housing Finance Authority multifamily revenue bond | $86,200,000 |

| Los Angeles Housing Department loan | $4,000,000 |

| Low Income Housing Tax Credit equity (Goldman Sachs) | $8,000,000 |

| Commercial | |

| Los Angeles Community Development Department, Section 108 loan | $14,630,000 |

| New Markets Tax Credit equity (Goldman Sachs) | $10,374,000 |

| Community Development Entities for NMTC allocations | |

| Los Angeles Development Fund | $15,000,000 |

| Clearinghouse CDFI | $14,000,000 |

| Genesis LA | $9,000,000 |

| Residential information | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unit type | Number | Affordable units | Size (sq ft) | Market-rate rent (minimum, October 2017) |

| Studio | 48 | 10 | 343–670 | $1,665 |

| 1 bedroom | 215 | 51 | 703–913 | $2,455 |

| 2 bedrooms | 149 | 27 | 899–982 | $2,879 |

| Townhouse | 26 | (included in 2 bedroom) | 1,241–1,422 | $3,200 |

| Total | 438 | 88 | average: 760 | |

| Office information | |

|---|---|

| Net rentable area | 35,000 sq ft |

| Percentage occupied | 100% |

| Key office tenant | Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority |

| Rental rate | $2.24 |

| Common area maintenance maximum | $4 |

| Tenant improvement allowance | $35 |

| Length of lease | 7 years with 15-year option |

| Terms | Triple net |

| Retail information | |

|---|---|

| Net rentable area | 43,620 sq ft |

| Percentage occupied | 78% |

| Key retail tenants | Retail type |

|---|---|

| Grow | Grocery |

| Cafe Gratitude | Vegan restaurant |

| EdiBOL | Asian restaurant |

| Westbound | Bar |

| Amazebowls | Sweets |

| Van Leeuwen | Ice cream |

| Bulletproof | Coffee |

| Hennessey + Ingalls | Art bookshop |

| A Shop Called Quest | Comics |

| Wittmore | Apparel |

| Voyager Shop | Apparel |

| Hue | Apparel |

| Benjamin | Beauty salon |

| Malin + Goetz | Cosmetics |

| Nailbox | Beauty salon |

Format

Full

City

Los Angeles

State/Province

CA

Country

USA

Metro Area

Los Angeles

Project Type

Mixed Use

Location Type

Other Central City

Land Uses

Arts Center

Multifamily Rental Housing

Office

Plaza

Restaurant

Retail

Structured Parking

Transportation Use

Underground Parking

Keywords

Affordable housing

Air rights

Art center

Arts-oriented development

Low-income housing

Mixed-income housing

Mixed-use development

Neighborhood retail center

Outdoor events

pedestrian streets

Public-private partnership

Transit-oriented development

Site Size

4.03

acres

acres

hectares

Date Started

2005

Date Opened

2014

Website

https://www.berkshirecommunities.com/apartments/ca/los-angeles/one-santa-fe/

Further reading

https://www.architecturalrecord.com/articles/10168-one-santa-fe

https://la.curbed.com/maps/arts-district-los-angeles-development-map-2

Project address

300 South Santa Fe Avenue

Los Angeles, CA 90013

Developers

Cowley Real Estate Partners

Culver City, California

www.cowleyrep.com

Polis Builders Ltd.

Los Angeles, California

The McGregor Company

Beverly Hills, California

www.mcgregorbrown.com

Canyon Capital Realty Advisors, through Canyon-Johnson Urban Fund III

Century City, California

www.canyonpartners.com/strategies/real-estate

Financial partner

Goldman Sachs Urban Investment Group

Owner

Berkshire Group

Boston, Massachusetts

Design architect

Michael Maltzan Architecture

Los Angeles, California

Executive architects

KTGY Architecture+Planning

Gensler

Landscape architect

LRM Landscape Architecture

General contractor

Bernards

San Fernando, California

Engineering

Gouvis Group

Weidlinger Associates Inc.

KPFF Consulting Engineers

Public relations

JSPR

Open Line PR

Photographers

Douglas Hill Photography, architectural images

Warren Air Video & Photography, aerial images

Interviewees

Emily Watson, senior vice president, Berkshire Communities

Michael Murillo, leasing director, Berkshire Communities

Charles Cowley, president, Cowley Real Estate Partners

Michael Maltzan, principal architect, Michael Maltzan Architecture

ULI Staff

Patrick L. Phillips

Global Chief Executive Officer

Ralph Boyd

Chief Executive Officer, ULI Americas

Stockton Williams

Executive Vice President, Content

Payton Chung

Director

Case Studies and Publications

Principal Author

James A. Mulligan

Senior Editor