Format

Deal Profiles

City

Phoenix

State/Province

AZ

Country

USA

Metro Area

Phoenix

Project Type

Retail/Entertainment

Location Type

Other Central City

Keywords

Adaptive use

Creative placemaking

Deal profiles

Dealprofiles

High street retail

Historic preservation

Main street design

Main street retail

Transit-oriented development

Date Started

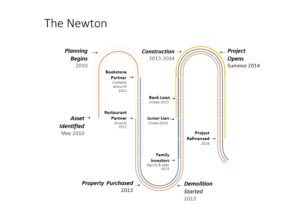

2010

Date Opened

2014

The Newton is an 18,599-square-foot (1,727 sq m) mixed-use retail, dining, office, and events building in Uptown Phoenix, Arizona, housing an independent bookstore with a beer, wine, and coffee bar; a home and garden store; a chef-led restaurant; a small office; and spaces for meetings and events. The Newton hosts hundreds of events each year, whether sponsored by its tenants or booked by the public. It was built within a renovated restaurant/banquet facility whose mid-century modern architecture and old-fashioned cuisine made it a local landmark for 40 years.

![The Commons during an informal event, with the window to the First Draft bar open. [Venue Projects, LLC]](https://casestudies.uli.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Newton-E-300x197.jpg)

The Site and Neighborhood

The Newton is located in what was the Beef Eaters steakhouse in Uptown Phoenix, less than five miles (8 km) north of downtown and just off the intersection between two of Phoenix’s signature roads—Central Avenue and Camelback Road. Beef Eaters opened in 1961 to serve the blossoming business strip along Central, as pioneering strip shopping centers and office towers followed Phoenix’s relentless march northward.

Subsequent decades of suburban expansion left the area behind, but investment in Uptown Phoenix reinvigorated following the 2008 opening of the Valley Metro light-rail line, which runs along Central through midtown and then turns west onto Camelback in Uptown. By 2009, a restaurant row was emerging on Central in what had been a cluster of low-slung mid-century office buildings. One of those was the Windsor, a 1940s deli that was redeveloped by Venue Projects and its principals, Lorenzo Perez and Jon Kitchell.

The Initial Idea

In 2010, four years after Beef Eaters closed and in the depths of the Great Recession, city officials introduced Venue Projects to the investor who had purchased the empty restaurant for a condominium development site during the boom years. Venue was hired to handle a planning process to identify potential new uses.

It became clear that the site was, Perez says, “an ideal place to create something that said something about central Phoenix and its heritage. It had the potential to revive what Beef Eaters was: a community gathering space where people come together around food.” It was adjacent to a burgeoning restaurant district, was less than a quarter mile (0.4 km) to two new light-rail stops, and had a demonstrated loyal following—but the site’s asking price was just too high.

A year later, Perez and Kitchell were giving a presentation about the Windsor to a crowd that included Cindy Dach, one of the owners of Changing Hands bookstore, a local institution that had served the college town of Tempe since 1974. After the talk, she approached Perez and Kitchell with an idea: she liked their style and wanted them to help Changing Hands find a second location in central Phoenix. Dach envisioned a retail space paired with a bar and space for events, in a synergistic location with creative neighbors—all in an interesting old building on the light-rail line, drawing customers from across the valley. Even more of a stretch: the bookstore, having been displaced from downtown to south Tempe by rising rents, wanted to have an ownership stake as well.

The Idea Evolves

Not long after missing out on a site across from the city’s central library in midtown, Kitchell had “an idea so contrarian that we fell in love with it: an iconic bookstore in the iconic Beef Eaters building.” Sure, it was west of Central, and “you had to get past the smell to see the possibilities,” but the bookstore was a perfect fit for the concept that Venue had envisioned. He went back to the previous owner with an offer to purchase the Beef Eaters property and was able to negotiate a substantially reduced acquisition price through a short sale.

The next step was to find a complementary restaurant anchor. Perez and Dach reached out to contacts in the local restaurant scene to ask which chefs might entertain the notion of expanding into Beef Eaters. During a tour of the space, chef Justin Beckett; his wife, Michelle; and their business partners Scott and Katie Stephens were noncommittal, but “you could see the reaction on their faces when they walked through,” says Perez. After a few meetings with Venue and Changing Hands to explore the idea further, Southern Rail restaurant signed on, under similar co-owner terms.

The Newton revolves around the Commons, a former banquet hall in the middle of the building. It retains a wide hearth and twin chandeliers, and has glassy openings to each of the tenant spaces. Having Southern Rail restaurant in the front, says Perez, “screams ‘people gathering place’ to folks who are riding by on the train.” The bookstore fills most of what was the dining room, with most of the building’s parking lot frontage; its First Draft Book Bar opens into the Commons. Southwest Gardener, a garden and home boutique, lines most of the back wall, its entrance off the parking lot glimmering with brightly colored decorations. In the back corner of the building are two meeting rooms that can be combined into a theater, and an office (originally intended as a third meeting room) leased to a law firm.

Financial Overview

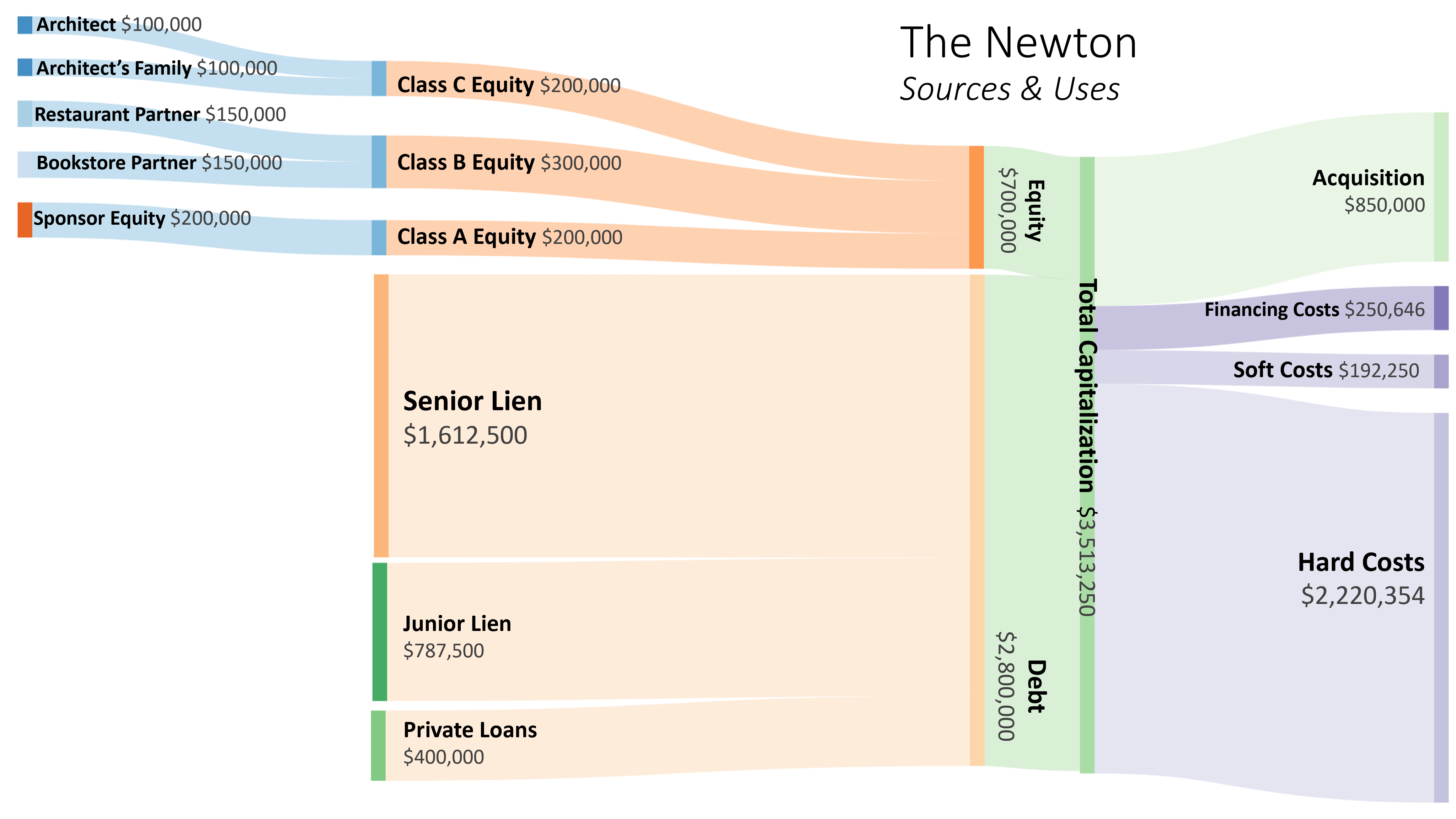

The Newton’s $3.5 million project budget was cobbled together from seven different sources, with a $1.6 million senior lien covering less than half the budget. A junior lien from a nonprofit loan fund and private loans paid for another 34 percent of the budget. Most important to the project were its equity investors, including the sponsor, two anchor tenants, the architect, and family members, who contributed 20 percent of the budget.

Pat McNamara, senior program officer at LISC Phoenix, says, “The most interesting part of this deal is the structure: his core tenants are part owners, so they’re not going to skedaddle. They’re going to stay interested for a long time.”

Equity: Locating Investors

The Newton’s anchor tenants were also its codevelopers, co-investors, and comanagers, an approach Venue had tried before. The project LLC has three classes of equity, with more-preferred classes having lower risk but higher par values. Venue Investments contributed $200,000 for 40 percent of the equity. It is the managing member of the LLC and fully guarantees its debt. The individual owners of the bookstore and restaurant (but not the corporate entities) each contributed $150,000 for 20 percent ownership stakes. They have limited management authority and limited liability. Douglas (the architect) and Kitchell’s sister each contributed $100,000, for 10 percent passive ownership stakes that have no exposure to a default.

“I was on board the minute [Venue] brought it to my attention,” says Douglas. “They asked if I would like to be a partner, and I said there’s no way I’m not going to be partner, which was a first for me.” His firm’s offices are within a building that Venue reconstructed, and he had worked with the Kitchell company for decades. (The junior equity investors later made $400,000 in private loans to cover construction price escalation.)

Perez says that this arrangement “aligns your interests. It was a sign of commitment [to lenders] that they were all in with us—but other developers do question your sanity.” Making tenants also co-owners does means that “you need to be more balanced and empathetic” when negotiating leases, Perez says. The leases have a base rent that ramps up over the first three years, plus a percentage of sales. The leases are arm’s-length transactions with the tenants’ corporate entities.

The arrangement was what drew Changing Hands to the deal. McNamara says, “Over the years, they saw that after they move in, a coffee shop moves in, then a bar moves in on the other side. They knew that they were creating value and [foot traffic], but hadn’t benefited” from that upside when in leased space.

![First Draft blends into the bookstore. [Venue Projects, LLC]](https://casestudies.uli.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Newton-11-300x203.jpg)

Senior Debt: Locating the Lender

Alliance Bank, a community bank, made a $1.6 million first-lien construction loan on flexible terms: a three-year interest-only period and 20-year amortization, no prepayment penalties, and a pro-rata guarantee so that the junior equity partners were only partially exposed to default. Steve Curley, executive vice president of Alliance Association Bank, had previously worked with Craig DeMarco of Upward Projects, the owner of the Windsor restaurant, and lent to that project—not as a real estate project, but as a business loan for owner-occupied real estate.

The Newton was a risky bet, given the Phoenix area’s deep recession; the building’s dilapidated state and down-at-the-heels neighbors, and sponsors who had only recently struck out on their own. Yet a regional bank like Alliance was, Curley says, “aware of how the area was redeveloping because of light rail,” familiar with Venue’s approach and quality, and was confident in the credit risk of the tenant co-owners. “We’re local to Phoenix, and we’re willing to bet on its small businesses as our customers—including both the tenants and the developers of the Newton.”

Senior Debt: Underwriting Process

Curley was also familiar with “the unique [ownership] structure,” which Venue had pioneered with the Windsor, but this time had to deal with even more ownership interests. “That’s a lot to coordinate for a relatively small loan,” says Curley, so it took a while to “get everybody on the same page, and educate them all simultaneously about why this is structured that way, all when each party wanted to comment on each detail,” particularly given that the tenants had little experience with construction loans. Coordinating all of those parties before starting construction “makes it a better project, but makes it more difficult,” says Curley.

“Having the tenants as co-owners is a superior way to do redevelopment,” says Curley. “It was great for the community, great for the bank, and they’re great customers”—with at least one tenant switching its banking relationship over afterwards. “We should’ve done more deals like it,” he continues, and readily would have “if there was a nice template for doing more of these—a more prescriptive set of documents about how this works, and how it’s good for tenants” to become co-owners.

Alliance was “willing to do [this deal], but only up to a certain amount,” says Perez. He would have to go out to find a mezzanine loan before starting construction.

Junior Debt: Locating the Lender

Like the first lease signed, the $787,500 second mortgage came about serendipitously. Perez was speaking on a panel, and another panelist said that the Newton could be a poster child for the new investment fund she was launching. It turned out that the Local Initiatives Support Corporation (LISC) and Raza Development Fund (a community development financial institution affiliated with the National Council of La Raza) had just launched a $20 million fund—since renewed with an additional $30 million commitment in 2015—to provide gap financing for equitable-development projects in the Valley Metro light-rail corridor.

The two were already active in areas like affordable housing and health clinics, but reached out to organizations like ULI to “reach out to developers we didn’t already know,” says McNamara of LISC. The Newton sat at a catalytic location just past the existing extent of redevelopment. McNamara says, “It’s only three blocks west, but it encouraged people to make the turn” onto Camelback. Frieda Pollack, program officer with LISC Phoenix, notes that “it’s a foothold between Central and Seventh Avenue, where we’ve been working for years to foster micro-enterprises through technical assistance.” McNamara was also impressed that the Newton “created jobs and local wealth—it’s all locally owned, so all that money stays here.”

Junior Debt: Underwriting

LISC’s approach to real estate lending is “more subjective than a bank’s. [Instead of] concrete terms, we want to see how our money could help the deal work, and let us feel comfortable and secure,” says McNamara. In the case of the Newton, which had equity partners and a senior lender, that ended up being a lien-only subordinate construction loan to the project.

As with Alliance, LISC had to be patient while Venue arranged the deal and got sign-offs from numerous partners. “There were lots of large meetings to talk about loan terms and underwriting details. It took a lot of talking amongst themselves to agree on those details while remaining friends,” recalls McNamara.

Of course, adding another lien increased the complexity for Alliance. LISC insisted upon the security of a subordinate lien, which required “a comfort level that we needed with Alliance, and they needed with us,” says McNamara. Curley echoes the sentiment, saying that the “fund played a huge role in the project’s success, but the structure was hard to explain to my loan committee,” who were more familiar with unsecured mezzanine loans.

LISC has shown remarkable flexibility with its loan. A year in, the project was meeting its pro forma, but operating cash flow was still tight, so LISC offered to expand its initial credit. When the permanent financing fell short of fully taking out both mortgages, LISC still wanted to stay tied to the project and refinanced $177,000 of its loan as a small second mortgage.

![Southern Rail's patio seating along Camelback Road. [Venue Projects, LLC]](https://casestudies.uli.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Newton-C-300x204.jpg)

Permanent Debt

Although the project has met its internal financial goals, a problem arose when it came time to convert to permanent financing with a life insurer: the appraisals came in lower than expected. Some of that was likely due to lingering stigma over the location west of Central; the comparable properties selected were suburban strip malls to the west, rather than urban properties in the denser, more fashionable neighborhoods just a few blocks east. In addition, the rent escalation clauses did not flatter the early income statements. Even though locally owned retailers like those at the Newton may have established operating histories and loyal customer bases, appraisers do not view them as “credit tenants” and thus discount their value.

None of that materially hurt Venue Projects, which intends to hold the property, but Perez sees the appraisal as indicative of a broader “disconnect between what society wants and what our finance system gives us. We were penalized for not doing just another armchair investment.

“Community banks and independent businesses are more likely to stay with” a landlord, he continues, “since these people realize that they also have a lot to lose both financially and emotionally.” So-called credit tenants, on the other hand, can easily walk away and leave behind a dark box. Big banks, loan syndicators, and merchant builders have to work at such large volumes that they often cannot spend the time it takes to craft unique and thriving places.

Lessons Learned

Capture value. Bringing the tenants into the deal as capital partners ensures that they benefit financially from the value of the place that they have helped create. It also gives them a stake in working hard to ensure that the place is successful.

Adjacencies. “We curate our tenants like art,” says Perez—especially in an era when retail is driven by events, experiences, and “third places” that can appeal across the demographic spectrum. He has been pleased to see the sheer variety of people and events that have been drawn to the Newton, from families and retirees to singles and students. Adding more dining options in future phases will further improve those adjacencies, says Perez. Even within the Newton, two smaller restaurants with two complementary menus could have worked better than one large restaurant.

Adaptability. Creative urban retail projects often have a unique character, so “you have to live with them for a few years to truly understand how they operate,” says Perez. One key is to listen to new ideas and to be open to changing course: being open to others’ ideas about how to tenant the back-corner space ultimately paid off.

Project Information

| Development timeline | Month/year |

|---|---|

| Beef Eaters restaurant opened | 1961 |

| Beef Eaters closed | 2006 |

| Venue introduced to seller by city | May 2010 |

| Venue hired as consultant to position asset for sale | 2010 |

| Property listed at $2.1 million | 2010 |

| Venue presents on reuse at Pecha Kucha event | 2011 |

| Bookstore contacts Venue to explore joint venture | 2011 |

| Venue contacts owner with concept | 2011 |

| Negotiations on short sale of property | 2012 |

| Initial offer of $900,000 made and withdrawn | 2012 |

| Second offer of $850,000 made | 2012 |

| Acquisition closed | 2013 |

| Demolition and abatement permits issued | 2013 |

| $400,000 bridge loan closed | 2013 |

| Engineering, bidding, value engineering, debt raise | 2013 |

| Construction loans closed | 2013 |

| Restaurant and bookstore opened | June 2014 |

| Final tenants opened | October 2014 |

| Development cost information | |

|---|---|

| Site acquisition cost | $850,000 |

| Hard costs | $2,220,354 |

| Soft costs | $192,250 |

| Predevelopment costs | $13,250 |

| Finance costs | $109,193 |

| Developer fee | $67,451 |

| Contingency | $60,752 |

| Total development cost | $3,513,250 |

| Total development costs per sq ft | $207 |

| Financing sources | |

|---|---|

| Debt capital sources | |

| Senior lien (Alliance Bank) | $1,612,500 |

| Junior lien (LISC) | $787,500 |

| Private debt | $400,000 |

| Total debt capital | $2,800,000 |

| Equity capital sources | |

| Venue Investments LLC | $200,000 |

| Equity partner #1 (bookstore) | $150,000 |

| Equity partner #1 (restaurant) | $150,000 |

| Equity partner #1 (architect) | $100,000 |

| Equity partner #4 (friends and family) | $100,000 |

| Total equity capital | $700,000 |

Format

Deal Profiles

City

Phoenix

State/Province

AZ

Country

USA

Metro Area

Phoenix

Project Type

Retail/Entertainment

Location Type

Other Central City

Keywords

Adaptive use

Creative placemaking

Deal profiles

Dealprofiles

High street retail

Historic preservation

Main street design

Main street retail

Transit-oriented development

Date Started

2010

Date Opened

2014

Website

Project address

300 W. Camelback Road

Phoenix, Arizona

Developer

Venue Projects

Phoenix, Arizona

www.venueprojects.com

Architect

John Douglas Architects

Scottsdale, Arizona

www.douglasarchitects.com

Interviewees

Lorenzo Perez, co-owner, Venue Projects

John Douglas, founder, John Douglas Architects

Steve Curley, executive vice president, Alliance Association Bank

Pat McNamara, senior program officer, Local Initiatives Support Corporation Phoenix

Principal Author

Payton Chung