Format

Deal Profiles

City

Boise

State/Province

ID

Country

USA

Metro Area

Boise

Project Type

Mixed Use

Location Type

Central Business District

Land Uses

Event Space

Mixed Use--Three Uses or More

Multifamily Rental Housing

Office

Restaurant

Retail

Keywords

Adaptive use

Deal profiles

Dealprofiles

Downtown housing

Neighborhood revitalization

Site Size

1.79

acres

acres

hectares

Date Started

2011

Date Opened

2015

The Owyhee is a 139,424 square foot mixed-use building in downtown Boise, Idaho that combines 55,683 square feet of office space, 36 studio and one-bedroom apartments, 23,913 square feet of restaurants and convenience retail, and a ballroom for special events. The building was built in 1910 as a grand hotel, and is fondly remembered by many local residents. Its redevelopment included the first newly built apartments in downtown Boise in decades, and established that a market existed for luxury apartments and creative office space. Many local lenders and investors passed on the Owyhee’s renovation, but out-of-town investors saw its potential both during redevelopment and after completion.

Deal Profiles from the ULI Center for Capital Markets and Real Estate showcase how developers bring together financing for small but high-impact developments.

View a recorded webinar featuring a presentation and discussion about this Deal Profile.

The Site and Neighborhood

Since 1910, the Owyhee Hotel at 11th and Main has anchored the west end of Boise’s Main Street. It was deemed the city’s first “skyscraper” at the time, with a capacious ballroom and roof garden that made it the city’s premier destination for celebrations. In the 1960s and 1970s, attempts at modernizing the hotel saw its original upper-floor rooms converted to offices and new motel wings built behind and beside the building. While the historic building’s ground floor and second floor remained as the hotel’s ballroom and restaurant, the process “made a really cool building really kind of a piece of junk,” says Carley—destroying features like a golden stained-glass dome (which now crowns a nearby museum ballroom), marble columns, a mosaic floor, and arched two-story display windows.

Pam Sprute, a local broker and Carley’s neighbor, brought the site to Carley’s attention. Carley protested that “I’m done doing historic buildings,” but Sprute persisted, pointing out that just the 1.5 acres (0.6 ha) of land underneath was worth the asking price, and that its loan was headed into default. He would have to strike now, or wait out years of legal limbo.

The Initial Idea

Carley’s family business had been instrumental in rejuvenating Old Boise, an early 20th-century section around Sixth and Main Street. Despite his skepticism about taking on the much larger Owyhee, he was encouraged by what he found on site. The building’s systems were operational, the ballroom was still in demand, and the 1970s-era office interiors were ugly but salvageable for smaller creative office tenants. Most important, one hotel wing was a throwaway, but the taller wing along Main Street could be redone into 36 small apartments, offering “a way to test the apartment market in downtown. There had been no new product in 25 years, and this could be cheap and easy.”

The Idea Evolves

No historic building rehabilitation is as simple as it seems, and especially not one that incorporates so many different uses——retail, events, office, and residential. The renovation uncovered plenty of unpleasant surprises: the “entirely fireproof” hotel was coated with asbestos, whose remediation a century later would cost $500,000.

Phasing was critical, especially since the ballroom was still up and running: “The previous owner had bookings in the ballroom for eight months after we closed,” Carley says, so he kept the business running: “I didn’t want to say, ‘Sorry, you can’t get married’” on account of a construction project. The failing hotel business, though, was closed off and the motel wing scraped, and office floors closed off for renovation.

Financial Overview

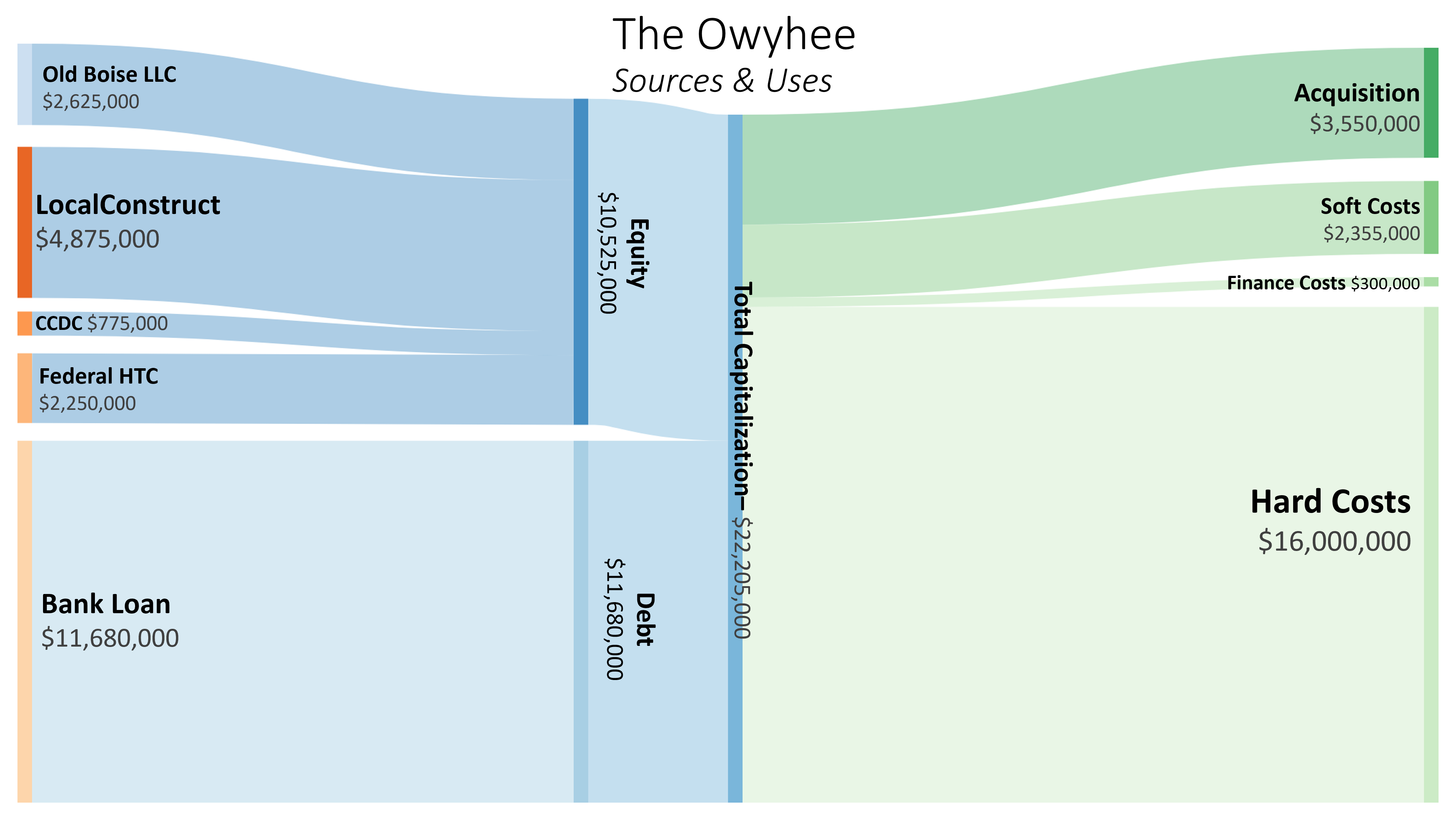

Although its two sponsors and local authorities saw great promise in the Owyhee, the project faced considerable challenges in lining up bank financing. A construction loan covered only half of the budget for the building’s acquisition and renovation, with most of the rest contributed by its sponsors. The project’s substantial equity requirement led Carley to reach out early on to find another developer to joint-venture on the project.

Public money also offset the cost of the project, but both the federal historic tax credits and a local redevelopment authority’s award were paid back to the sponsors after construction.

Senior Lien: Locating the Lender and Underwriting

Even despite Carley’s long track record in Boise, “we struggled to find a lender who both appreciated the project and understood the market,” he says, and “started out of our own pocket even before we had a loan in place.” Finding the lender required “cold-calling around town—it was painful.”

Many local banks were skeptical about the planned apartments, in particular. There was certainly no class A apartment downtown, and “the only market-rate [apartment] comp nearby was a 50-year-old building with rents of $1.20 per square foot.”

While shopping around for a loan, Carley had talked with a community development financial institution (CDFI) in Montana about pursuing a loan backed by New Markets Tax Credits (NMTCs). “They loved the project and wanted to get involved,” but coordinating with both an out-of-state CDFI and bank proved difficult. Carley did not know this at the time, but once he started demolition with his own funds, that took NMTCs off the table; they are available only for projects that would not have occurred “but for” the credits.

The cold-calling eventually turned up Bank of the West, which “took the time to understand it,” says Mike Brown, founding partner of LocalConstruct, the development partner. They underwrote up to an initial loan amount that still required substantial sponsor equity and sponsor guarantees, but without a pre-leasing commitment. “It was low leverage, but they did extend the loan,” says Brown.

The sponsors came back after lease-up had started with very good news—the first office leases had been signed at 20 percent above pro forma, and the first apartments at almost 40 percent above comps—and the bank extended additional credit to complete tenant improvements. In total, the bank extended $11.68 million in credit to the project.

Equity: Locating the Investor

Carley knew from the start that he would need to joint-venture on the project. Not only was the Owyhee a larger and costlier project than his prior renovations, but he also did not have multifamily experience—nor did anyone else in town, for that matter. Carley met with five longtime local developers, all of whom told him, “This is too old, too messed up, good luck, see you later.”

Sprute had previously been hired by LocalConstruct, a Los Angeles–based developer, to begin scouting the Boise market for development sites, and had shown the Owyhee to them. She mentioned this to Carley as he was closing on the site, and he reached out with the idea of a partial apartment conversion.

Brown says that LocalConstruct, which had made a name for itself in central L.A. for design-forward residential projects like Blackbirds (see Urban Land, August 2016), had long been looking to branch out from L.A. and into secondary markets. They scoured cities across the West that would “outperform over the course of our careers,” says Brown, and where they could “be recognized as the highest-quality developer in the market.”

Not only did secondary markets offer faster growth, they were less cutthroat: “Besides being unpleasant, it’s expensive and time-consuming” to develop in Los Angeles, Brown says. The two cities they decided upon were Colorado Springs, Colorado, and Boise, both fast-growing small metro areas with populations of about 600,000.

Despite their similarities, the two cities required different approaches. Colorado Springs had almost four times the apartment inventory that Boise did, so an acquire plus value-add strategy made sense there. By contrast, Brown says that Boise was “not a mature apartment market at the time, so it took a lot of shoe leather to get in.” At the time that Carley approached them, they had already purchased some downtown land.

Brown says the initial idea was that LocalConstruct could “provide some capital and manage the apartment side,” bringing in marketing and management experience. As the project’s large scope became apparent, “we wound up taking a more active role than we had originally planned to.” LocalConstruct took a 65 percent joint venture stake, ultimately committing to $4.875 million, after the cost escalations and its share of tax credits. Carley’s share of equity investment would eventually total to $2.625 million.

Equity: Underwriting

“We did not expect to joint-venture, but this opportunity came up and suited our development business pretty well,” says Brown. LocalConstruct recognized the value of retail as an amenity, and thought that “Clay had a good vision for what the place could be . . . the whole could be more than the sum of the parts,” with the hotel’s old lobby serving as it always had—as a common area where residents and visitors could mingle.

Brown also echoes Carley’s observation: “If we can convert this to apartments, we can own for a lower cost per door than ground-up construction—and then, we’ll have a comp” that would prove the value of downtown apartments. Brown says that from their “work in other markets, we knew people will absolutely pay for high-quality space—especially downtown, where people can walk anywhere they want.” Yet convincing Boise banks of that point would require building it.

LocalConstruct also saw the potential to cement a legacy in a new city. “We wanted to do development in Boise for the foreseeable future,” Brown says, “and every single Boise native has some story about that building . . . it’s a really cool historic building that people care about. If we do a good job here, people will take notice and will open doors for us.”

Public Financing

Brown says that “it’s unlikely that this project would’ve gotten done but for other [financing] elements,” namely public funding. The Capital City Development Corporation was excited to see the Owyhee rejuvenated, and also especially excited to prove the demand for new apartments downtown. Through its General Assistance and Public/Private Project Coordination program, the CCDC provided a $750,000 property tax increment reimbursement over five years for infrastructure, sidewalks, site work, and facade work. The Owyhee scored highly on the CCDC’s rubric for grant applications, which prioritize adaptive use and ground-floor retail.

Carley had not used historic tax credits (HTCs) on previous projects, which “were small enough that it wasn’t worth the trouble.” The Owyhee was different, though its timing was not great: a recent tax court opinion had frozen the market for syndicated HTCs, and the bank did not give it any special consideration. “So we just absorbed it,” says Carley, essentially self-syndicating the $2.25 million in credits: “It just comes later by not paying taxes.” The CCDC also facilitated a historic facade easement donation, resulting in $25,000 in additional income tax savings.

Permanent Financing

Carley says that the Owyhee was a subpar “economic success compared to pro forma, because the costs were so exorbitant.” The cost overruns soured what was otherwise a triumph: rents are far above projections, the lobby is abuzz throughout the day, and it definitively demonstrated that Boise needed class A apartments downtown.

Having served that strategic purpose, the mixed-use Owyhee no longer fit into LocalConstruct’s core portfolio: “All we do at this point is buy, build, and hold apartments,” says Brown. Then news broke that a family office from Wisconsin had purchased a large retail-entertainment complex six blocks away, with broker Clay Anderson telling the Idaho Business Review that “we are helping them find more product in the Boise market.”

Hendricks Commercial Properties has assembled and built portfolios of mixed-use buildings in smaller cities like its hometown of Beloit, Wisconsin; Delafield, a suburb of Milwaukee; and Indianapolis. Founder Diane Hendricks and her late husband parlayed a few house rehabs into a building supply fortune; she told the New York Times, “I see old buildings, and I see an opportunity for putting things in them.”

Brown says that they soon reached out to Anderson with an offer to sell “the kind of asset that fits their personality,” and one with “a fair amount of value that a new owner will be able to unlock,” by redeveloping two parking lots and rolling over prerenovation office leases. Several months later, the Owyhee had a new owner. “The way they valued it surprised me,” says Carley, given its current rent roll, “but 10 years from now, its economic success would be an A.”

Lessons Learned

Pioneering can be costly. The Owyhee ran into a classic chicken-and-egg problem with appraisals in an untested market—in this case, class A downtown apartments. The lack of adequate comps precludes innovative products and development at novel locations. Brown understands lenders’ reticence at the time: “Now it’s a vibrant downtown, but seven years ago you couldn’t see that it was going to head in that direction. . . . We were not absolutely certain that people were going to buy in.”

In retrospect, the apartments have done so well that Carley wishes he had rebuilt—rather than converted—the apartment wing as a taller, stand-alone building. Splitting the apartments and offices might also have simplified valuation.

Incentives matter. Carley sees two missed opportunities for zero-cost equity for the Owyhee. Waiting another year to start demolition could have allowed for the NMTC financing, kicking in a few million dollars in equity. A state or local historic tax credit that matched at least some of the federal dollars also would have made a difference.

An outside view. Interestingly, the Owyhee attracted two different out-of-town equity investors at different points. Unlike local investors, both saw the potential of a marquee asset to introduce themselves to a tight-knit but booming market.

Project Information

| Development timeline | Year |

|---|---|

| Site purchased | 2011 |

| Planning started | 2012 |

| Construction started | 2013 |

| Construction financing arranged | 2013 |

| Sales/leasing started | 2015 |

| Project completed | 2015 |

| Project sold | 2019 |

| Gross building area | Square feet |

|---|---|

| Office | 55,683 |

| Retail/restaurant | 23,913 |

| Residential | 32,500 |

| Surface parking (100 spaces) | 43,560 |

| Common area | 27,328 |

| Total GBA | 139,424 |

| Development cost information | Amount in $ |

|---|---|

| Site acquisition cost | 3,550,000 |

| Hard costs | 16,000,000 |

| Soft costs | 2,355,000 |

| Financing costs | 300,000 |

| Total development cost at completion | 22,205,000 |

| Hard costs per sq ft | 115 |

| Total development costs per sq ft | 159 |

| Financing sources | Amount in $ |

|---|---|

| Debt capital sources | |

| Bank of the West | 11,680,000 |

| Equity capital sources | |

| LocalConstruct | 4,875,000 |

| Old Boise LLC | 2,625,000 |

| Future federal tax credits | 2,250,000 |

| Public sector capital sources | |

| Capital City Development Corporation | 775,000 |

| Total | 22,205,000 |

Format

Deal Profiles

City

Boise

State/Province

ID

Country

USA

Metro Area

Boise

Project Type

Mixed Use

Location Type

Central Business District

Land Uses

Event Space

Mixed Use--Three Uses or More

Multifamily Rental Housing

Office

Restaurant

Retail

Keywords

Adaptive use

Deal profiles

Dealprofiles

Downtown housing

Neighborhood revitalization

Site Size

1.79

acres

acres

hectares

Date Started

2011

Date Opened

2015

Website

http://www.theowyhee.com

Address

1109 W. Main St.

Boise, Idaho 83702

Developers

Owyhee Place LLC

Boise, Idaho

Architect

Beebe Skidmore/The Architects Office

Portland, Oregon and Boise, Idaho

Interviewees

Clay Carley

General manager, Old Boise, Inc.

Mike Brown

Co-founder, LocalConstruct

Principal Author

Payton Chung