Format

Deal Profiles

City

Buffalo

State/Province

NY

Country

USA

Metro Area

Buffalo

Project Type

Mixed Use

Location Type

Other Central City

Land Uses

Event Space

Multifamily Rental Housing

Restaurant

Retail

Keywords

Adaptive use

Deal profiles

Dealprofiles

Historic preservation

Site Size

1.8

acres

acres

hectares

Date Started

2015

Date Opened

2018

This adaptive use transformed a two-story, 48,000-square-foot commercial building and ornate movie theater lobby into 23 loft apartments, four neighborhood-serving retailers, and a large banquet facility that fills the former lobby. The structure is the most prominent building along the Seneca Street corridor in south Buffalo, New York. The renovation was completed by a local developer and financed by a local bank, together with historic tax credits, local tax incentives, and grants.

The Site and Neighborhood

The 2,500-seat Shea’s Seneca Theater opened in 1930 as Buffalo cinema mogul Michael Shea’s gift to his old neighborhood. It was there in south Buffalo that Shea worked his way up from the docks to build a vaudeville and cinema empire. His crown jewel was the 4,000-seat Shea’s Buffalo, whose elaborate marquee still casts a warm glow up and down Main Street in downtown, four miles from Shea’s Seneca.

Unfortunately, “the Seneca Show” was also his swan song, as it opened just as the Great Depression set in. After three decades of nightly shows, its auditorium went dark during the 1960s and was demolished in 1970 for a parking lot. Yet like many other early cinemas, the theater was always part of a mixed-use real estate development: the auditorium filled the middle of a block, fronted by a two-story liner commercial building whose shops and offices could profit from the theater’s steady stream of customers. That liner building, including the cinema’s fantastical lobby, escaped the cinema’s fate thanks to discount stores downstairs and the famed Skyroom music club upstairs.

Shea’s Seneca was a prominent landmark along Seneca Street, a commercial corridor stretching southeast from downtown. Matt Hartrich, vice president of business development at Schneider Development, says, “South Buffalo is its own microcosm, a very close-knit community” across the Buffalo River from downtown.

Seneca Street’s commercial corridor looked shopworn, with dollar stores a block on either side. Jake Schneider, president of Schneider Development Services, saw that it was surrounded by “a stable community with good density and a lot of historic housing stock.” Around the corner from Shea’s Seneca was Cazenovia Park, one of Buffalo’s six treasured parks designed by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux. Its popular ice rink, swimming pool, farmers market, and annual Irish Festival draw crowds year-round. Three blocks down was another neighborhood anchor, Mercy Hospital.

The Idea

Shea’s Seneca was almost entirely boarded up when Schneider first took notice of it. The “vertically integrated service company” was launched by Schneider from his family’s architectural firm, and had completed several loft apartment or office conversions downtown with ancillary retail. In 2015, though, it seemed as if “all the opportunities downtown were picked over,” says Schneider.

Taking on Shea’s Seneca was “a big leap of faith,” Schneider continues: it had a deep ground floor that could not just be converted to residential. “The question mark for me [was whether] would we be able to rent that amount of retail. . . If so, we would be more community builders than ever before.”

Hartrich felt fairly confident in the local apartment market. “Apartments had some precedent” in the area, since “another developer had converted a couple of schools . . . they’re nice and new adaptive reuse,” which rent at a premium to vintage apartments.

The Idea Evolves

The next step was to figure out what to do with the interior space—particularly one breathtaking architectural element. “We had a large lobby we knew we needed to keep intact, 120 feet long and two and a half stories high,” and Schneider’s first thought was to contact a banquet hall and restaurant operator. Classic Events, which ran three venues as well as restaurants, signed on to take 11,800 square feet, including the lobby and the middle of the building.

Early on, the company signed a letter of intent with a small theater company to anchor the other end of the ground floor, leaving some smaller shops in between. About a year later, the theater company decided that the numbers didn’t work.

Hartrich did not have to look far for smaller tenants. A walk over to the park sufficed: “Every Sunday, the farmers market in Caz Park was booming. . . . We started poking around, talking with some of those folks if they wanted a bricks-and-mortar location.” A florist and a coffee shop graduated from the market into Shea’s Seneca. Similarly, two neighborhood residents opened a craft beer shop, and a Mexican restaurant moved from nearby Lackawanna. Hartrich says that “local ties help with the long-term success, especially neighborhood residents with neighborhood connections” who understand area needs and tastes. Although the area has many available retail spaces, the renovated Shea’s Seneca was able to offer tenants new and customized interiors.

Schneider says that it “wasn’t until we started leasing them up that we became confident that we made the right call.” Ultimately, it was right: “All of the spaces pre-leased in early phases of construction,” says Hartrich.

Financial Overview

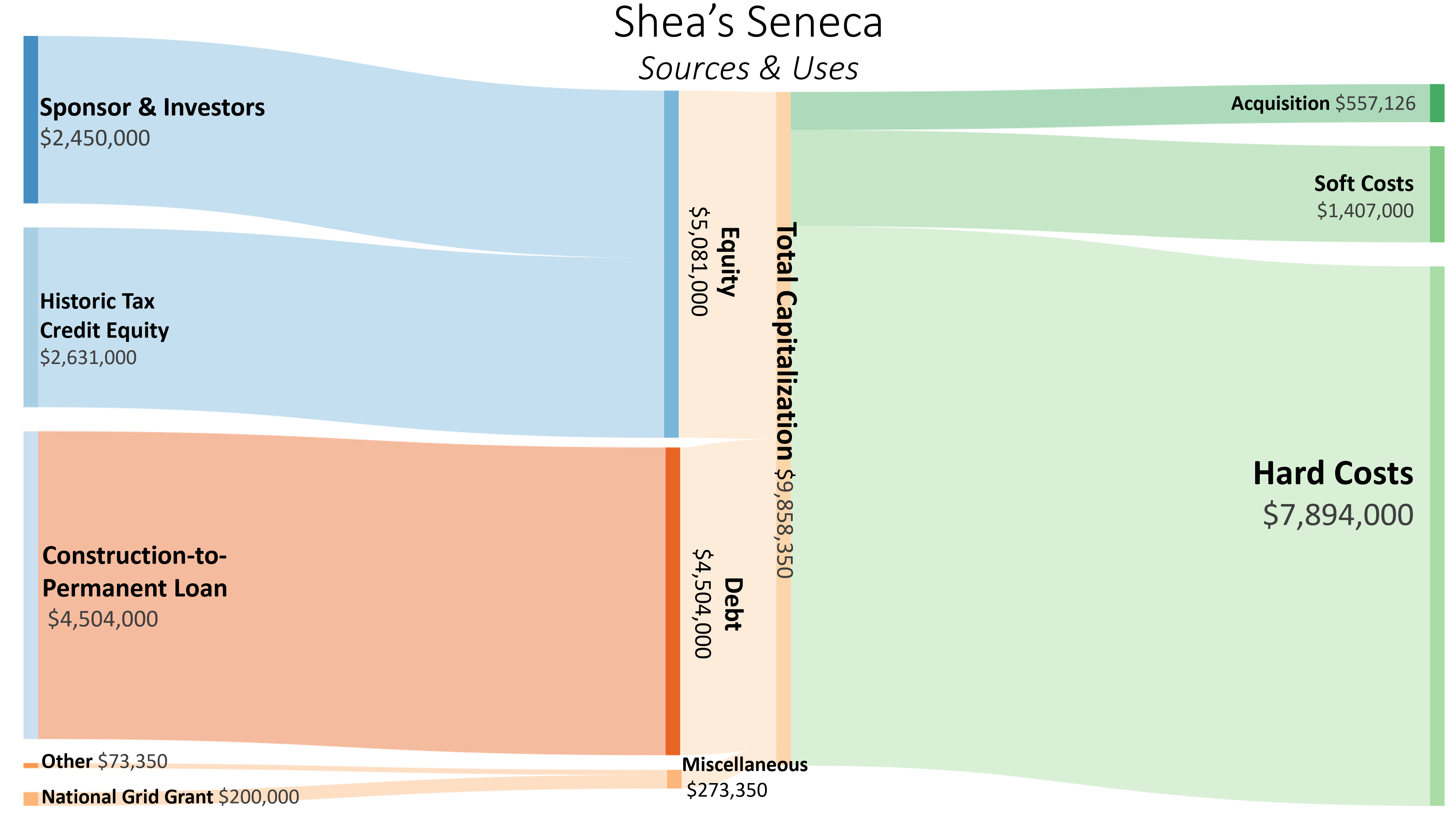

The bank loan for Shea’s Seneca covered less than half of the total project cost. About one-fourth of the cost was paid for via equity raised by selling historic tax credits to the construction lender, another one-fourth from investor and sponsor equity, and the balance through a variety of small grants.

Senior Lien: Locating the Lender

James Rykowski, director of community development at Evans Bank, says that they have known about Schneider for decades. Evans had recently financed Schneider’s commercial conversion of a church building, which involved buying historic tax credits that the church could not use.

Schneider says that relationship results from Evans being “one of the smaller local banks” that offered a single transaction for both lending and historic tax credit (HTC) equity. “I’ve done a lot of HTC projects . . . [and] it’s so much easier to have it all under one umbrella,” he continues. Rykowski concurs: “It was a cognizant decision to control both sides of the fence. Local developers knew we were purchasing tax credits, so it’s good business and provides a good return for the bank.” He notes that the single closing also saves the developer the cost and hassle of refinancing; the loan for Shea’s Seneca has a 10-year term. (This is even more useful now that HTCs are paid out over five years.)

Senior Lien: Underwriting

Rykowski says that as a local bank, Evans understood the underlying strengths of south Buffalo. “All of us go through those neighborhoods and business districts,” he says, continuing that they “knew the neighborhood and developer, could see what could be done, and also what market rents were achievable. Someone from out of the area would only know what they read in their appraisal,” and not have as complete a view of the project’s rewards. Indeed, Rykowski specifically remembered the Skyroom.

Rykowski says that the amount of retail space was “unusual,” especially given the unproven market. But “their early discussions with the banquet facility took the sting out,” and ultimately the bank did not require any retail pre-leasing. However, the loan did require a personal guarantee.

While Evans Bank saw potential in south Buffalo, an out-of-town appraiser was not quite as enthusiastic. As a result, Schneider says, “we weren’t able to borrow as much money as we had hoped.” The bank approved a $4.504 million loan, at an 80 percent loan-to-value ratio, but the appraised value did not take a local tax abatement into account—significantly discounting the project’s stabilized net operating income. “We asked the bank lending committee to reevaluate, and they said we need to go with the appraiser,” says Schneider. Filling the gap would require additional equity, and finding a variety of grants.

Public Financing

“We used a lot of different tools” to fill the financing gap, says Schneider, pointing out that “our construction costs [in Buffalo] are on pace with the rest of the country, but our rents are not. We need all these gap financing tools to make a project happen.” Most significant were the federal and state historic tax credits that Evans Bank syndicated, for a $2.631 million equity investment. New York has a state historic tax credit that directly stacks atop the federal credit.

Three local government programs helped, two provided through the Erie County Industrial Development Agency. These exempted the project from local sales tax on construction materials—a savings that Schneider puts at around $350,000—as well as a mortgage recording tax exemption. Shea’s Seneca also qualified for the city’s Section 485-A property tax abatement, which fully abates property taxes on improvements for eight years and then phases out through year 13. Schneider points out that this program amounts to a significant savings during stabilization: “This property was derelict, and we’re paying taxes on that old assessment” while the project pays down its loan principal, and “should be able to operate on an even keel” after the abatement phases out.

Three grants also helped offset the equity requirement, and better tie the project into the neighborhood. National Grid, the local electric utility, gave $200,000, which Schneider says “we used for the marquee that we restored” and which once again lights up Seneca Street. The local gas company, National Fuel, also granted $16,250. Its location within a Buffalo Main Streets Initiative target area also qualified it for a $40,000 grant via the state’s $40 million Better Buffalo Fund, meant to rejuvenate historic commercial districts.

That rejuvenation continues; Schneider says they are “working with local officials to do a streetscape project on Seneca,” which will “involve new traffic-calming techniques for a safer streetscape, and improved landscaping.”

Equity

“Buffalo is a community where people have very strong feelings” and want to invest in transformative real estate, says Schneider. The firm’s equity investors “are local, historically has always been personal relationships of some kind . . . a lot of our original investors are still investing with us.

“We really align ourselves with like-minded people who buy into our foundational philosophy regarding community building. Our benchmarks are not get-rich-quick plans, but they’re saleable,” he continues. For investors, “South Buffalo was a slightly different sell, but not difficult” compared with downtown—again, in part because the building itself was so well known. That Schneider committed sponsor equity was key, he says: “Our investors know if we put our own money in, we believe in it.” Ultimately, $2.45 million in equity was invested into the project.

Lessons Learned

Explain gap financing. Predictable and familiar tax incentives, like historic tax credits, can be used as collateral for a loan, and—even better—can be folded into a loan. However, Schneider had more trouble explaining the 485-A tax abatement to the appraiser. The resulting appraisal limited the project’s debt capacity and required additional equity.

Anchors matter. Shea’s Seneca was built with a cinema to anchor its retail, and rebuilt with a banquet hall as an anchor. Having the most difficult interior space spoken for by an experienced and creditworthy tenant was crucial to securing the loan.

Local knowledge. Local investors, a local bank, and local retailers all were more likely to see the intangibles—its density, its sense of community, its building stock—that made south Buffalo a worthwhile investment.

Patience. Value creation occurs over the long term. ”I knew there would be a lot of work after we finished the building,” says Schneider. The company has doubled down on Seneca Street by purchasing and formulating plans to renovate a grand bank building across the street.

Project Information

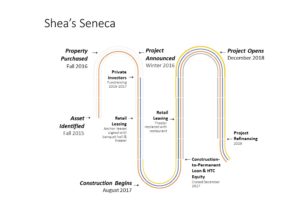

| Project timeline | Date |

|---|---|

| Planning began | October 2015 |

| Site purchased | August 25, 2016 |

| Groundbreaking | August 1, 2017 |

| Construction loan closed | December 21, 2017 |

| Opening | December 31, 2018 |

| Financing sources | Amount ($) |

|---|---|

| Debt capital sources | |

| Evans Bank | $4,504,000 |

| Equity capital sources | |

| Evans Bank (historic tax credit investor) | $2,631,000 |

| Private investors and sponsor | $2,450,000 |

| Other capital sources | |

| National Grid grant | $200,000 |

| National Fuel grant | $16,250 |

| New York State, Better Buffalo Fund grant | $40,000 |

| Rental income during construction | $17,100 |

| Total | $9,858,350 |

| Development cost information | Amount |

|---|---|

| Acquisition | $557,126 |

| Hard costs | $7,894,000 |

| Soft costs | $1,407,000 |

| Total | $9,858,226 |

| Hard costs per square foot | $164 |

| Total development costs per square foot | $205 |

Format

Deal Profiles

City

Buffalo

State/Province

NY

Country

USA

Metro Area

Buffalo

Project Type

Mixed Use

Location Type

Other Central City

Land Uses

Event Space

Multifamily Rental Housing

Restaurant

Retail

Keywords

Adaptive use

Deal profiles

Dealprofiles

Historic preservation

Site Size

1.8

acres

acres

hectares

Date Started

2015

Date Opened

2018

Website

http://www.schneiderdevelopmentservices.com/

Address

2178 Seneca Street

Buffalo, New York

Developer

Schneider Development Services, LLC

Buffalo, New York

Architect

Schneider Architectural Services, P.C.

Buffalo, New York

Interviewees

C. Jake Schneider

President, Schneider Design, Architects and Schneider Development

Matt Hartrich

Vice President of Development, Schneider Development

James Rykowski

Director of Community Development, Evans Bank

Principal Author

Payton Chung