Format

Deal Profiles

City

Oklahoma City

State/Province

OK

Country

USA

Metro Area

Oklahoma City

Project Type

Retail/Entertainment

Location Type

Other Central City

Land Uses

Office

Plaza

Restaurant

Retail

Keywords

Deal Profile

Dealprofiles

Infill development

Main street design

Main street retail

Restaurants

Site Size

0.4

acres

acres

hectares

Date Started

2014

Date Opened

2017

Three new buildings, with 7,553 square feet of retail space on 0.41 acres, bracket a small plaza that replaced a vacant lot at the edge of an established retail area north of downtown Oklahoma City. The three restaurants and eight studio/office spaces complement the area’s established arts anchors.

The Site and Neighborhood

The Paseo Art District’s retail core was originally developed in 1928 as the Spanish Village, a pioneering shopping district inspired by Country Club Plaza in Kansas City, Missouri. Two blocks of Spanish revival retail buildings line Paseo, a broad street that curves across the city’s street grid. Since 1975, an annual Paseo Arts Festival has established the area as a regional destination for visual and performing arts, with more than 20 art galleries. Pueblo’s site sits 50 feet off Paseo at one of its angled intersections; it had long ago been cleared of three houses that had once occupied the property.

Foraker Company began in 2013 as a retail brokerage, so Jeremy Foraker, its president and managing broker, was keenly aware of retail leasing opportunities along Paseo. “I was having conversations with tenants who had interest in expanding or looking for space and not being able to find it,” he says. Little new space had been built or even turned over in years, and many existing spaces were large and deep—perhaps suited to art studios, but not as well suited to art galleries, boutiques, local service providers, or dining.

The Initial Idea

Foraker had renovated a nearby residential building and had already started on another infill retail project a block away on Paseo. He figured that new and shallow buildings could fulfill a niche for smaller-footprint tenants—“bite-sized spaces to start a business in,” he says, with the small size meaning tenants’ monthly payment is a “lower nominal rent rate, but higher dollar per foot for the developer.” (Pueblo’s smallest space is 309 square feet, with gross rent of $700 per month.) New buildings could also frame off-street pedestrian spaces, a key amenity for both restaurants and galleries.

The site was listed for sale in 2014, and Foraker was soon bidding against another buyer. He arranged a land acquisition loan with a local lender, quickly commissioning an architect to lay out two buildings on the site—a larger structure for three retailers or restaurants facing the street and behind it, separated by a parking lot, a narrower office/gallery structure.

The Idea Evolves

After securing the site, Foraker quickly gained approval for a construction loan on the two-building project. Once the engineering process had begun, though, it became apparent that the plans were cost-prohibitive: the site sloped up by 10 feet from the Paseo corner, and the two long buildings required giant retaining walls and long ramps to get people and vehicles across the property.

Foraker and Sam Gresham Architect revisited the initial scheme, removing the drive aisle and moving all the parking to curbside angled spaces (including six along a residential street on the uphill side). The larger retail building was split into two single-level structures, one at the uphill grade and one at Paseo’s grade, bracketing a two-level pedestrian plaza and a grand staircase. The result not only was simpler to build, but also created two outdoor patios—intimate, pedestrian-scaled open spaces that could be a key selling point. However, the new plan also reduced the project’s retail frontage, potentially cutting into net operating income (NOI), though also reducing costs.

Financial Overview

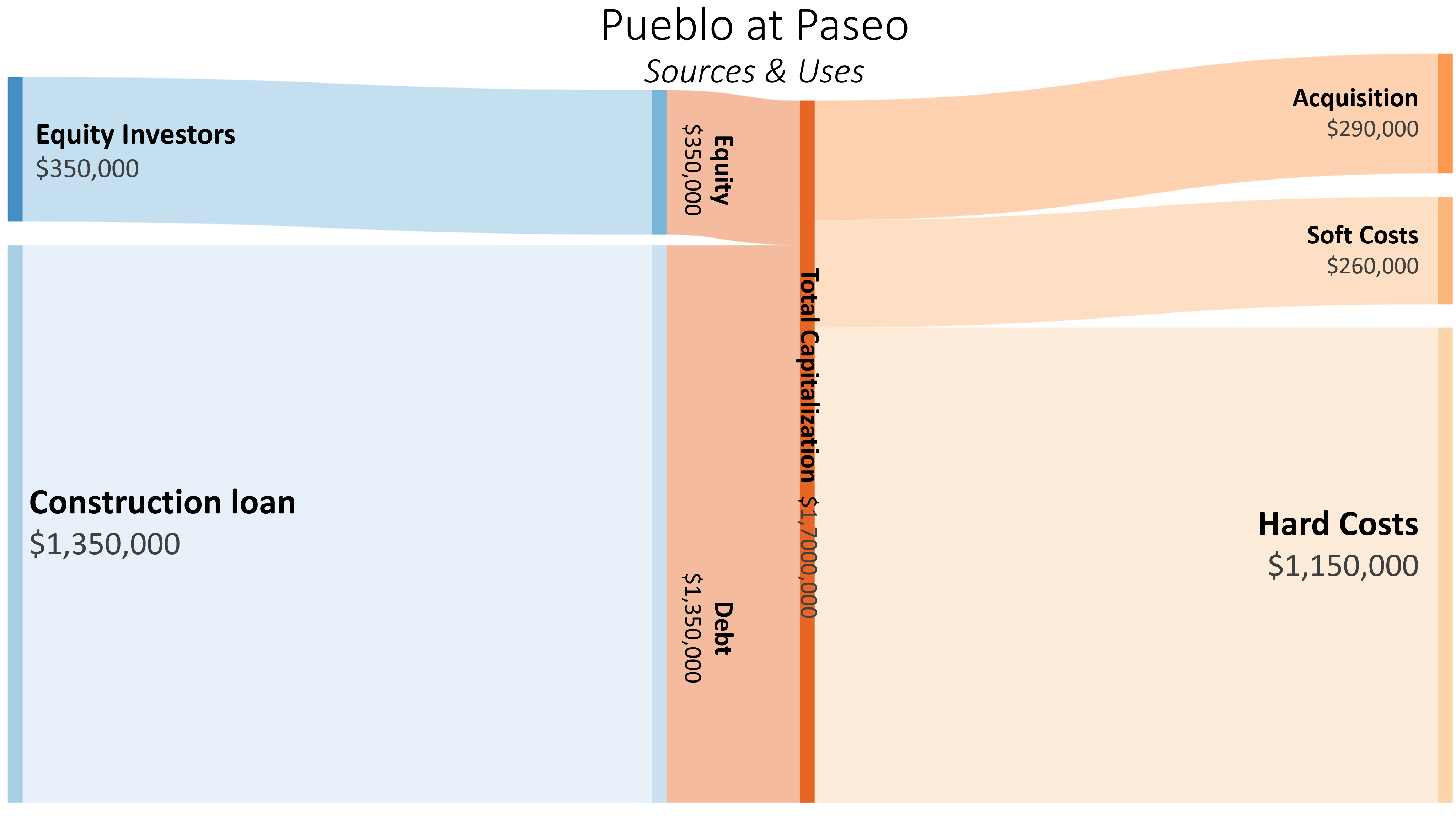

The $1.7 million project was funded primarily through a $1.36 million construction-to-permanent loan from a local bank, which also refinanced a $150,000 loan on land acquisition. The balance of the project costs was paid from $350,000 in outside equity raised from four local investors.

Debt

Jesse Cowan, now senior vice president at First Liberty Bank in Oklahoma City, was a banker at Valliance Bank when he met Foraker a few years ago. Foraker was then managing single-tenant retail projects for a larger firm but was interested in branching out to pursue infill development. Cowan, who had noticed that across the city “a lot of pockets like Paseo were seeing revitalization and a lot of new businesses going in,” was intrigued by Foraker’s plans for infill projects. Foraker echoes the sentiment: “Urban districts had been gaining a lot of momentum, [and] lenders that had been reluctant for a while were moving from traditional suburban” projects toward urban infill.

Cowan happened to check in with Foraker not long after the Pueblo site had been secured. “He mentioned that he was doing this project, and we had a discussion about us taking out the land note and possibly doing a construction loan,” Cowan says. Foraker had initially assumed he would roll the land note into a construction-to-permanent loan with the same bank. However, Valliance offered a longer (25-year) amortization period, a 10-year term, and an 18-month interest-only construction period. The lower payment came in handy when lease-up took longer than expected.

Foraker ultimately applied for construction loans from three community banks and was turned down by one bank unfamiliar with the neighborhood or the tenant mix. Foraker recalls that each bank required some convincing that “there was the demand for new space,” he says. “The tenants we had were not credit tenants, so we had to educate them to the market and the demand and put together almost a résumé of the tenants to show some history.” It helped that the largest spaces had letters of intent from local restaurateurs with proven concepts elsewhere.

Cowan, in contrast, recalls that Valliance was confident in the market’s continued growth. He was particularly confident that Foraker would be able to meet his projections, plus offer a margin of safety: “He could still service the debt easily with lower rents” than what was projected.

For the smaller offices, Cowan says, “we weren’t really expecting to have LOIs [letters of intent] of significance on those, but he did have a few before we closed”—all signed during the redesign process. That flexibility was needed: “Even though most of the spaces were spoken for” at closing, says Foraker, “a couple of the LOIs I had in place ended up not even opening.” Luckily, other businesses were able to backfill those smaller spaces.

The loan committee had already approved the project before the redesign. “It definitely was a difficult conversation to go back and change gears and go back to committee,” Foraker says, but luckily he had not yet drawn on the loan. “Jeremy and I had a good working relationship and kept the lines of communication open to understand what was going on” throughout the several months it took to redesign the project, says Cowan. “We didn’t put a lot of pressure on him to get it done, but we weren’t funding it until then.”

The loan went back before the loan committee after another set of reviews. Cowan says. “We had to reassess the layout once he was done . . . make sure the scope would appraise correctly,” he says. Though the project had fewer square feet, it also came in at a much lower cost.

Equity

Foraker worked with Jonathan Dodson, another Oklahoma City infill developer (see ULI Deal Profile: EastPoint), to arrange the equity investments. Dodson is a former commercial banker and worked on a fee basis to locate four investors—one at $200,000 and three at $50,000—who cumulatively own 75 percent of the project entity. Each investor gets an 8 percent preferred return and a commensurate share of proceeds at refinance or sale.

In the future, Foraker would rather “offer the equity group more ownership, in lieu of doing a ‘pref.’” The preferred yield has consumed much of the initial cash flow from the project. Although he had little problem signing letters of intent with tenants, not all could start paying rent right at opening. In a project this small, replacing one tenant dented cash flow enough to delay the preferred returns.

Lessons Learned

The right spaces. Foraker knew from his brokerage background that two niches of tenants were keen on Paseo but could not find the right spaces—restaurants, for which buildouts are easier in new buildings than in older ones, and small service providers. In retrospect, Foraker thinks the public spaces could use more flourishes. “I missed my opportunity to add public art on the front end,” he says.

Thinking ahead. The redesign was perhaps unavoidable, but it did result in the deal having to undergo underwriting three times—first for the acquisition loan, then the first construction loan, and finally the second construction loan. Luckily, the redesign occurred before the loan was disbursed and not while the loan was accruing interest.

Long-term hold. A single tenant backing out of its LOI hurt initial cash flow enough to affect the equity investors’ preferred returns. Foraker would have preferred that the project’s tenant mix has more time to hit its stride. To avoid this “pref pressure” in the future, he plans to offer a larger ownership stake in exchange for less cash flow early on. “These are more difficult projects that take more time,” he says, well suited for “smaller investors who want to hold something in these districts over a long period of time and are excited to help grow these districts,” rather than income-oriented investors.

Project Information

Format

Deal Profiles

City

Oklahoma City

State/Province

OK

Country

USA

Metro Area

Oklahoma City

Project Type

Retail/Entertainment

Location Type

Other Central City

Land Uses

Office

Plaza

Restaurant

Retail

Keywords

Deal Profile

Dealprofiles

Infill development

Main street design

Main street retail

Restaurants

Site Size

0.4

acres

acres

hectares

Date Started

2014

Date Opened

2017

Website

http://forakercompany.com/pueblo-at-paseo

Address

607 NW 28th St.

Oklahoma City, OK 73103

Developer

Foraker Company

Oklahoma City, Oklahoma

Architect

Sam Gresham Architecture

Interviewees

Jeremy Foraker, CCIM

President and Managing Broker

Foraker Company

Jesse Cowan

Senior Vice President

First Liberty Bank

Principal Author

Payton Chung